A Most Decorated American Warrior Colonel Robert L. Howard, U.S. Army Special Forces, Vietnam Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star Conclusion

Published 4:30 pm Friday, April 8, 2022

- President Richard M. Nixon awards the Medal of Honor to Sgt. Robert L. Howard on Mar. 2, 1971. [Photo: sofrep.com]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The war in Vietnam was not lost in the field, nor was it lost on the front pages of the New York Times or the college campuses. It was lost in Washington, D.C.” —H. R. McMaster

COURAGE -[the author’s definition]: That mental strength of character that allows someone to undertake a task, so fraught with danger that that person has a high likelihood of losing his life in the process. Courage was commonplace in Vietnam, be it a soldier who volunteered to walk point in a known enemy stronghold; a naval aviator who strapped on his flight suit and launched from the pitching deck of an aircraft carrier, the day after his best friend was shot down in the skies over North Vietnam; a truck driver who volunteered to drive the lead ammunition supply truck in a convoy into an area known for enemy ambushes; or the recon soldier who volunteered to lead a platoon, to be dropped by helicopter into the heart of the Ho Chi Minh Trail to attempt the rescue of a wounded comrade .Sergeant Robert L. Howard’s service in Vietnam epitomized the very definition of COURAGE!

When Howard returned to Vietnam for the second tour, he was part of an elite, highly classified force, the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group [MACV-SOG]. Part of this group’s responsibilities [in addition to rescuing downed U.S. airmen from North Vietnam] was to run recon missions along the Laos-Vietnam border to identify routes used by the NVA for infiltration and escape.

As reported/shared in the first two articles in this series, Sergeant Howard distinguished himself on at least two missions, in such a heroic manner as to be nominated for the Medal of Honor twice. In those cases, the award was downgraded to the Distinguished Service Cross and the Silver Star. America’s greatest commando was not fighting for awards.

In late December 1968, three weeks after his second nomination for the Medal of Honor, Howard volunteered for a mission into a particularly dangerous area of the Ho Chi Minh Trail in southern Laos known as “The Bra.” That area was where Highway 110 split eastward from Highway 96, the main north-south route of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Most all of the NVA troops, equipment and supplies passed through “The Bra” going into South Vietnam. The NVA also had a major base hidden in that area, known as Binh Tram 37, where they stockpiled weapons and supplies. For that reason, it was heavily defended by antiaircraft guns and battalions of security troops. Any U.S. mission near the area of “The Bra” was met with a sense of dread.

Howard had not healed from his wounds from the last mission when he volunteered for a prisoner snatch operation in “The Bra.” “The recon-team included one-zero [code name for the recon team leader] Larry White, one-one [the assistant leader], Sergeant Robert “Buckwheat” Clough, Howard, an ARVN [South Vietnamese] officer and six Montagnards. When their Huey was met with ground fire at the LZ [landing zone], they flew to a back-up site some distance away.

As they landed, they were met with enemy fire from three directions. The ARVN officer was killed and most of the men were wounded except Howard and Clough. More than a hundred NVA rushed the Huey from concealed bunkers. White had fallen out the door of the helicopter when he was wounded and was trying to get back in when he was wounded again. He managed to kill several NVA before being shot the third time and falling unconscious. Howard and Clough had been spraying deadly fire at the oncoming NVA but stopped momentarily to drag White back aboard the helicopter. The wounded pilot managed to take off despite a shattered windscreen and all sorts of warning lights.

During the melee, the recon team had noticed an unbelievable sight some distance away. Hidden beneath the jungle canopy were two Soviet Mi-4 helicopters. As soon as their Huey was airborne, the recon team called in an airstrike to destroy the enemy choppers. Howard received no award for his actions.

Three weeks later, Howard was part of a Hatchet Force sent into Cambodia on a Bright Light mission [SOG code-name for a POW rescue mission] to recover a missing Green Beret. A recon team had been overrun and when they were extracted under heavy enemy fire, realized they were missing PFC Robert Scherdin. Meanwhile, Covey [an Air Force Forward Air Control unit that monitored SOG missions] picked up an emergency radio beacon from the area where Scherdin was last seen.

Without knowing if Scherdin had sent the signal of if it was a trap, a forty-man Bright Light platoon was sent out the next day. Lt. Jim Jerson commanded the unit with Sgt. Howard, second in command. As the recon team landed, they came under fire but were able to beat off the attack. After several more engagements with the NVA, the platoon managed to reach the hill where Scherdin’s beacon was transmitting. Howard told Jerson he suspected an ambush but he didn’t intend to leave a man behind.

As the men advanced up the hill, they were suddenly hit with explosions and gunfire. Howard was knocked unconscious and five men near him were killed. The Chinese claymore had ripped off his clothes and knocked away his rifle. His bloody fingers were shredded and he hurt all over. In an interview, Howard would later recall, “When I finally came to, I couldn’t see…blood was running down my face into my eyes. When my vision finally began clearing, I smelled the most horrible smell.” An enemy soldier was burning the dead Montagnards with a flamethrower. As the NVA with the flamethrower moved toward him, Howard pulled the pin on a grenade and held it quietly. The enemy soldier stared briefly, standing over Howard before moving on.

As the enemy soldier moved some distance away, Howard hurled the grenade toward him. After hearing the loud explosion, he realized that he needed to check on his wounded Lieutenant. Unable to walk because of his wounds, Howard managed to crawl to Jerson and drag him back down the hill. Knowing he needed to get help, Howard covered Jerson with vegetation and started crawling toward the rest of his platoon. He almost made it when he was spotted by an NVA who fired several rounds, hitting Howard in an ammo pouch, setting off the M-16 cartridges. The force of the explosion sent Howard down the slope where he landed beside a young NCO who was firing his M-16 while praying and sobbing. Howard asked the young soldier for his M-16 but was offered a .45 cal. pistol instead. Howard told him, “It’s not time to pray or cry, it’s time to fight or die.”

The “straight talk” from Howard seemed to bring the young NCO back to reality. Howard managed to stand as he and the soldier started back up the hill to retrieve Jerson. As they made their way, they dispatched several NVA who popped up. When he found Jerson, Howard put the .45 in one hand and picked up the badly wounded man with the other. As they started back down the hill, they again came under heavy fire and were forced to leave Jerson alone for a few minutes. They were able to return for Jerson with the covering fire from a young wounded ARVN officer. The young Vietnamese officer paid with his life.

They finally got Jerson down the hill. Howard had spent nearly six hours on the hill, badly wounded and bleeding, unable to hear anything from the original explosion and totally exhausted. A conscious Jerson was finally in friendly hands but they were all in extreme danger. Jerson refused morphine so he could help encourage Howard to continue to fight. As dark set in, Howard set up defensive positions against the expected NVA assaults.

During the night, the enemy kept up their attack. It got so bad at one point that Howard called in an AC-130 Spectre gunship on his own position. Howard no longer expected to get out alive, he just wanted to fight. And fight they did. They set up three strobe lights to direct cannon fire from the gunship and fought off assault after assault. Many of the Montagnards lay dead and dying all around the perimeter.

By 4 am their ammunition was almost gone and two strobe lights had been blasted to bits. Howard found it difficult to think but he realized that the situation was critical. He called Covey and told them, “If you’re going to get us out of here, you’d better come get us now.” Fortunately, helicopters were already on the way. As they arrived to extract the living and the dead, a C-130 began dropping parachute flares.

The sudden arrival of the Hueys amid the light from the flares caught the NVA by surprise. The first three choppers carried out wounded and dead Montagnards. The third helicopter was so overloaded that they had to toss out dead bodies. Howard and Jerson were the last to be loaded onboard the final helicopter. As it took off, an exhausted and badly wounded Howard remembered that they hadn’t brought back PFC Robert Scherdin – then he finally passed out.

Howard awoke in a field hospital, his wounds covered with bandages and feeling miserable. To add to his misery, he learned that Lt. Jerson had died. So many good men had given their all in the effort to rescue PFC Scherdin. For Howard, the men who died had done their best.

Captain Ed Lesesne, the recon company commander, wrote up the Medal of Honor nomination for Howard. This time there was no downgrading. President Richard M. Nixon presented the Medal of Honor to Sergeant Robert L. Howard on March 2, 1971 at the White House. After the ceremony, the President asked Howard if he’d like to join him for lunch or have a tour of the White House. The ever-humble Howard asked to be taken to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. There was almost no mention of this most decorated American Hero by the U.S. media which was wrapped up in its anti-war publicity.

There was no word in Howard’s vocabulary for “hopeless.” He once explained his mindset, “I had one choice to lay and wait or keep fighting for my men. If I waited, I gambled that things would get better while I did nothing. If I kept fighting, no matter how painful, I could stack the odds that recovery for my men and a safe exodus were achievable.”

Howard had been promoted from Sergeant to First Lieutenant in 1969 and retired as a Colonel in 1992. His highest assignment was as commander of the Special Forces Detachment in Korea. Even after his retirement, he visited troops including those in Iraq and Afghanistan. He worked with The Department of Veterans Affairs helping disabled veterans. Howard never missed an opportunity to encourage and inspire the troops and was in much demand as a patriotic speaker.

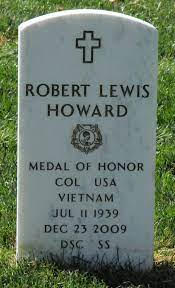

Grave marker of Col. Robert L. Howard, U.S. Army Special Forces, Vietnam. Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star. Arlington National Cemetery. [Photo: arlingtoncemetery.net]

John Vick

Sources: [Wikipedia; D Magazine, “The Greatest Hero America Never Knew” by David Feherty, June 23, 2010; Soldier of Fortune Magazine, “SOG’s Fiercest Warrior – Colonel Robert L. Howard” by Major John L. Plaster, U.S. Army Special Forces [ret], Dec. 3, 2021; Interview transcript, memory.loc.gov; arsof-history.org; arlingtoncemetery.net; “SOG – The Secret Wars of America’s Commandos in Vietnam” by John L. Plaster, Major, U.S Army, Special Operations Group]