Willie L. Ward, PFC, U.S. Army Air Corps, WWII Japanese POW

Published 4:30 pm Friday, February 11, 2022

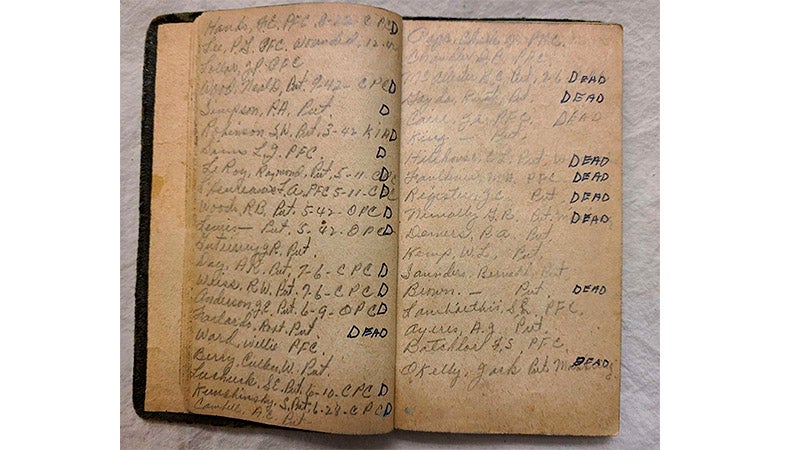

- PFC. Willie Ward's name is listed in this diary kept by Charles D. Page, a POW at the Cabanatuan prison camp in the Philippines. Page recorded the names of the 27th Bombardment Group that were held at the camp. His diary records in pencil, the names and fate of the the 212 men from the 27th. "D or Dead" was written by the names of the men who died. Of the 39 men listed here, only 16 survived, including PFC Willie Ward. [Photo: The National WW II Museum]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Author’s note: The original article published on January 29, 2022 has been updated with important information unavailable to the author at the time it was written.

During World War II, the William Moses Ward family had three sons who served in the U.S. Army Air Corps. The Ward family had the unwelcome distinction of having two sons who became prisoners of war: Preston J ”P J”Ward of the Germans and Willie L “Willie” Ward of the Japanese. Marvin I. Ward served in Army Air Corps in the European theater.

2nd Lieutenant P J Ward was the pilot of a B-17 that was shot down over Germany. His story was told in a previous article. Willie Ward was surrendered in the Philippines with nearly 85,000 American and Filipino troops defending the islands. When he was finally liberated from a POW camp at the end of the war, Willie had survived the Bataan Death March, the Cabanatuan POW camp in the Philippines, a voyage to mainland Japan aboard the hell-ship, Taga Maru, the Osaka POW camp #12-B at Hirohata and the Nagoya POW camp #9B at Toyama. When Willie Ward was finally liberated in September, 1945, he had been a prisoner of the Japanese for some 41 months. It’s hard to imagine a more amazing story of survival than that of PFC Willie Ward.

William Lewis “Willie” Ward was born in the Mobley Creek community in Covington County, Alabama, on October 25, 1918. His parents were William Moses and Mary Frances Hassel Ward. They lived near the William E. Ward, Sr. family. Both Ward families had several sons who served their country during WW II.

Willie attended area schools and graduated from Andalusia High School before joining the Army Air Corps in early 1940. He married Gladys L. Kay on September 10, 1941. At the time, Willie was a member of the 27th Bombardment Group Light stationed at Barksdale Air Force Base near Bossier City, Louisiana. The 27th began shipping out to the Philippines by way of Savannah, Georgia, in November 1941. Willie Ward was assigned to the Headquarters Group, 27th Bombardment Group and left Savannah for the Philippines in late November. He arrived just before the Japanese attack that happened on December 8 [because of the international dateline, that was the same day that Pearl Harbor was attacked].

Willie was a bombsight technician and was a part of the ground component of the 27th Bombardment Group stationed at Fort McKinley, just south of Manila. Their planes did not make it to the Philippines before the Japanese attack and were redirected to Australia. Support personnel from the 27th Bombardment Group, including PFC Willie Ward, were formed into the 2nd Battalion [27th Bombardment Group] Provisional Infantry Regiment [Air Corps], and sent to Bataan on December 25. They were hurriedly evacuated from the Manila area and did not bring adequate food and supplies which made their defense of the Bataan peninsula more difficult.

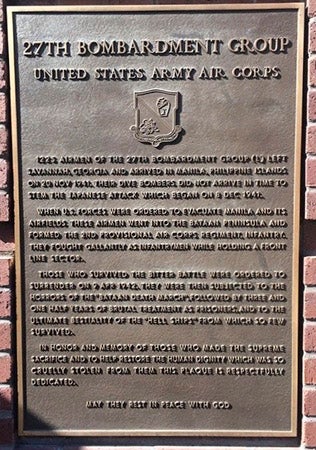

Memorial marker to the 27th Bombardment Group that departed from Savannah, Georgia, from November-December 1941. The marker is located at the Andersonville National Historic Site near Andersonville, Macon County, Georgia. [Photo: Makali Bruton, Dec. 2017]

In August 1942, Willie’s sister, Mrs. Lucille Ward Stephens received a telegram stating that he was “missing in action.” Willie and the captured Americans and Filipinos were marched some 85 miles north to two prison camps, O’Donnell and Cabanatuan. Between 200 and 500 American prisoners died on the march. Records show that Willie was taken to the Cabanatuan prison camp. Of the estimated 5,000 POWs held at the camp, there were more than 2,764 burials recorded. Willie was one of the survivors who were eventually moved to mainland Japan to be used as forced laborers.

On June 24, 1943, Willie’s sister Lucille received confirmation that Willie was a POW. In a telegram from the provost Marshall General, she was informed that the International Red Cross had reported that “your brother, Pvt. Willie L. Ward is a prisoner of the Japanese Government in the Philippine Islands.” That was the first information she had received since he was reported missing in action.

In December 2020, an article was published by the National WW II Museum in New Orleans that described a diary written in pencil by a Cabanatuan POW, Charles D. Page. The diary describes the lives of 212 POWs who were members of the 27th Bombardment Group. The diary lists the men by name, rate or rank, and shows whether or not they survived by noting “D or Dead.” On the two pages reproduced for this article, there are 39 names listed with only 16 survivors. One of the survivor’s listed on the first page is PFC Willie Ward.

After the war, Willie related a story to his cousins, Wyley and Richard Ward, about the Bataan Death March. He said that the Japanese guards would shoot anyone who fell out from exhaustion. Willie said that he marched with his hands on the shoulders of the man in front of him and cat-napped while marching. He would swap positions with the man in front so that he could do the same. That was how he survived the march.

In May 1942, Japan had begun transferring POWs to mainland Japan by sea. The transports were called hell-ships because of the horrendous living conditions for the prisoners. They were crammed into cargo holds with little air ventilation, little food and water on voyages that could last weeks. Because those ships carried a mix of prisoners, Japanese troops and cargo, they could not be marked as non-combatants and were therefore prime targets for allied planes and submarines. More than 20,000 allied POWs died at sea when 15 of those transport ships were sunk.

PFC Willie Ward was moved from the Cabanatuan camp on September 20, 1943 and placed on the transport ship, Taga Maru. The voyage lasted some 15 days and 70 of the 850 prisoners did not survive. Willie was taken to the Osaka prison camp #12-B at Hirohata.

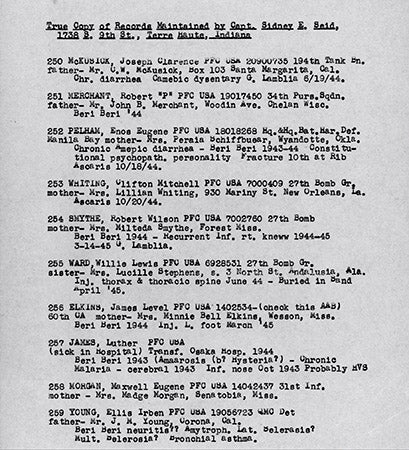

Captain Sidney Seid was the camp Doctor at the Hirohata prison camp. His records included PFC Willie Ward on page 34.

Prisoner # 255 is PFC Willie Ward. Seid recorded “Buried in sand, April 1945.” [Photo: Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office (DPMO]

Willie Ward and three other POWs also underwent another form of torture at the Hirohata camp. The Stars and Stripes reported testimony from a War Crimes trial that took place at Yokohama on March 22, 1946. Their March 23 edition carried a report headlined, “Japs Made POWs Squat 20 Minutes in In Ice Water.” An affidavit signed by PVT James W. Jones stated that he, PFC Willie Ward, PVT J. Clark and PFC Jesse M. Gibson were tortured by a civilian Japanese guard, Shinichi Motoyashiki and another guard.

Jones testified that, “We were forced to strip naked and squat in this tub. The ice had been broken first. Motoyashiki and another guard forced the prisoner’s heads under water for about 10 seconds. Jones continued, “Gibson passed out. Then we were taken out and beaten with a club. We were frozen-stiff. Then we had to stand naked, at attention in a biting wind for about an hour.” Another POW testified that the same guard forced prisoners to stand at attention with arms outstretched for hours.

Records indicate that Willie was transferred again on May 21, 1945, to a prison within the Nagoya prison group. There were 14 individual POW camps in the Nagoya district and Willie was transferred to the Nippon Express prison #9-B Toyama [Jinzu-Iwase] located in the city of Toyama, in the Toyama Prefecture. Willie was among the 230 American and 119 British and Australian prisoners at #9-B. Conditions at that camp were better as evidenced by the fact that only one POW died at the camp before it was liberated in August.

After the camp was liberated, Willie’s family received notice that he had sailed from Manila in September and was on his way home. The Andalusia Star noted in its November 1, 1945 edition that “Willie Lewis Ward had arrived in Andalusia last Friday for a brief visit with his sister, Mrs. Harvey Stephens.” We can only imagine the reunion at the Ward home when Willie came back to be reunited with his brother, P J Ward, who had returned home in June from two years in a German POW camp.

It has been a great honor to tell the stories of two such heroes as the Ward brothers. The author is reminded of a line from the movie, “The Bridges at Toko Ri,” based on James Michener’s book of the same name. The actor Frederic March played the part of Admiral Tarrant, who had just lost one of his best pilots and a rescue helicopter. He exclaimed, “Where do we get such men?” The same might be said of the Ward brothers.

After the war, Willie Ward worked with his father-in-law, Elijah Kay who ran a planer mill near Florala, Alabama. It’s possible that the mill was moved to Houston County because that’s where Willie died on May 17, 1990. His wife Gladys died January 20, 1995. They are both buried at the Garden of Mercy Cemetery at Kinsey, Alabama. They had no children.

John Vick

Author’s special note: This remarkable story of survival against incredible odds is a testament to the courage, sheer fortitude and triumph of the human spirit of one man – PFC. William Lewis “Willie” Ward from Covington County, Alabama. It is an honor and privilege to tell his story.

[The author thanks Richard and Wyley Donald Ward for their recollections of their cousin, Willie Ward. Thanks also to Patrick Regan, whose grandfather was aboard the Taga Maru with Willie Ward and was also sent to the Hirohata prison camp. Thanks also to Mindy Kotler Smith who corrected some dates and information. She is a Japan analyst and advisor to the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor].

{Sources: Wikipedia; the book, “The Steadfast Line” by Mary Cathrin May; The National WW II Museum article, Curator’s Choice, “The Book of the Dead and the Dying” Dec. 9, 2020; National Archives Prologue Magazine article “American POWs on Japanese Ships Take a Voyage into Hell”, 2003, Vol. 35, No. 4; Preliminary Japanese POW Camp List of all known POW camps in Japan, prepared for the War Crimes Legal Proceedings, SCAP files; Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, Historical Report, “U.S. Casualties and Burials at Cabanatuan POW Camp”; The Andalusia Star article dated July 1, 1943; The Montgomery Advertiser article dated August 30, 1942; The Andalusia Star article dated November 1, 1945; the Stars and Stripes, article dated March 23, 1946; “The Bridges at Toko Ri” by James Michener]