Preston J. Ward, 2nd Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Corps Pilot, WWII POW

Published 4:30 pm Friday, February 4, 2022

- The B-17 Royal Flush which was piloted by 2nd Lt. P J Ward on a bombing mission over Hamburg, Germany on July 25, 1943. The plane broke apart when hit with flak. There were only three survivors of the 10-man crew, Lt. Ward and two others. [Photo: The American Air Museum in Britain]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The William Moses Ward family had three sons that served in the U.S. Army Air Corps during WW II: Marvin I. Ward, Preston J. “P J” Ward and William L. “Willie” Ward. The Ward family had the unwelcome distinction of having two sons who became prisoners of war, half-a-world apart, Willie in Japan [see Star-News article for Jan. 29] and P J in Germany. This week’s article is about 2nd Lt. P J Ward.

P J Ward was born February 22, 1912, in the Mobley Creek community of Covington County, Alabama. His parents were William Moses and Mary Frances Hassel Ward. The William E. Ward, Sr. family were kin and lived nearby. Together, the Ward families had seven sons who served in WW II. P J Ward attended local schools and graduated from Andalusia High School. He married Claudia Leonard from Falco, Alabama, in April 1937. They had no children.

P J Ward had two years of college before joining the Army Air Corps Aviation Cadet program in early 1941. He began primary training at Maxwell Army Air Field, Montgomery, Alabama. He continued with basic training at Greenville Army Air Field, Greenville, Mississippi. From there, he was sent to George Army Air Field in Lawrenceville, Illinois, where he received his wings and was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in December 1942. P J was selected for multi-engine training and sent to Walla Walla Army Air Field, Washington where he learned to fly the B-17 Flying Fortress bomber. Ward trained with his crew at Hendricks Field near Sebring, Florida, before coming home for a brief visit in May 1943. He was then deployed to Europe with the 8th Air Force.

On Ward’s first mission, he flew the B-17 named M’Honey as a part of the 384th Bombardment Group’s attack on the Luftwaffe’s Villacoublay Airfield near Paris, France. The overall mission was a success and Ward’s B-17 returned undamaged.

On July 24, Ward piloted the B-17, Kathy Jane, on a mission to bomb the aluminum and magnesium factories in Heroya, Norway. On the way to the target, Ward had to abort the mission and turn back because of engine problems.

Ward’s third mission was on July 25. He flew the B-17, Royal Flush, with the 384th to Hamburg, Germany to attack the Blohm and Voss Aircraft works and the naval shipyards. Ward’s plane was brought down by enemy flak. The Missing Aircraft Report [MACR] stated that enemy flak over the target did little damage but the bombers were attacked over the target by more than 300 enemy fighters. The MACR showed that Ward’s plane crashed near Bad Oldesloe, Germany. The report concluded that only three of the ten-man crew survived, the pilot [Ward], the navigator [Robert Bederman] and the engineer/top turret gunner [Bert Landrum, Jr.].

The September 23, 1943 edition of The Andalusia Star, reported that Lt. P J Ward’s sister, Mrs. Harvey Stephens had received word from the War Department that her brother was now a prisoner of war in Germany.

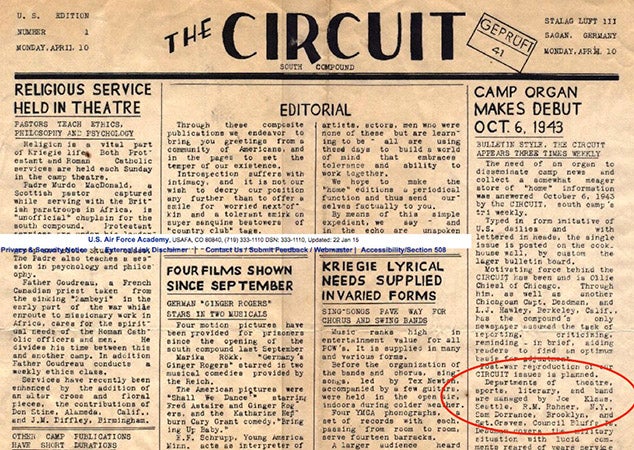

After his capture, Ward was taken to Stalag Luft III located at Sagan, Lower Silesia [now Poland]. Sometime later, he would come in contact with his good friend from Andalusia, Lt. Wesley Courson. In one of the ironies of the war, Lt. Courson’s B-17 was shot down on July 26, the day after Lt. Ward was shot down and they both were taken to Stalag Luft III. They remained there until January 1945 when they were moved to the Nuremberg-Langwasser prison camp.

2nd Lt. P J Ward was taken to Stalag Luft III when captured. He was moved to another POW camp near Nuremberg in 1945. [Photo: The American Air Museum in Britain]

The information about Ward’s time in prison camp is taken from an interview he gave The Andalusia Star after he returned home in June 1945. He recalled, “Once the allied bombings over Germany began in earnest, the German people began fleeing the bombed cities by the tens of thousands.”

At one point when he and other Allied Prisoners were being transferred to another camp by train, they were attacked by German refugees. Ward recalled that they were attacked with stones and other missiles. The mob cursed and abused the prisoners and it was only by the hardest efforts that a German officer, who happened to come upon the scene, was able to stop the attack and remove the prisoners from harm.

He spoke of prison camp conditions which deteriorated as the war progressed. Along with Wesley Courson, he was force-marched from their camp in East Prussia to a camp at Nuremberg. When the Russian army approached from the east. They were given 30 minutes to prepare to march. Ward recalled, “It was at night and it was below zero weather and I don’t think I’ve ever been so cold before…We marched many miles…There were about 2,000 prisoners. We were given only a quarter of a loaf of bread for each soldier per day and very little water. Some of the men fell out and what became of them, I never knew.”

When they reached Mavskaw in East Prussia, they were housed overnight in a glass factory. They were told that they would march 11 miles the next day, then 10 mile the day after before boarding a train. The train pulled small cattle cars in which were crammed 50 prisoners. They were so crowded that they took turns sitting and standing. Ward recalled, “We were on this train from Wednesday until Saturday with only a small piece of bread each day and with water served only twice during the trip. We were let out for air only once in four days.”

When they reached the prison camp in Nuremberg-Langwasser, they were shocked. Ward recalled, “We found it the filthiest place imaginable, with lice and fleas and without any sanitation. There was no food nor nothing on which to cook food if we had been provided any….Someone got word to London and told them of our plight…By this time we had only an occasional raw potato and I never before knew what real hunger meant. Then within a week, here came the Red Cross buses…The prisoners called the Red Cross buses ‘the white angels.’…it was their coming that saved the entire group from death by starvation.”

Lt. Ward related the approach of the Russian army and the camp’s liberation, “We had heard big guns in the distance for many days but we reasoned they were miles away. Then one day we hear rifle-fire outside the camp and we knew the Americans had come. The fighting lasted for some two hours and there were a few American soldiers killed but many more German soldiers lay dead at the scene of the battle….Then they broke open the gate…I recall a small private in his fighting garb, his face soiled with the dust of battle…we all made a rush for him and he was given the most hearty welcome that ever an American soldier received.”

Ward continued, “Then came the flag, Old Glory, and I never knew how great is the significance of that flag and what it stands for. It represents all that is the finest and best in the greatest country on earth….the entire armed might of this great country was dedicated to the principle that American soldiers suffering the tortures of a prison camp, manned by bestial Germans, have a right to expect that the men who march under that flag will come to their rescue…I was never before so proud of being an American.”

Ward concluded, “We fought to preserve the freedoms that American people have. We don’t approve of everything that has gone on back on the home front, but we do believe in America and we want to come back and take our places along with other citizens. We do not expect special favors. What we want is to be a part of the great body of free people…and lend our aid to all those who feel as we do after victory, that we should build a peace on such a solid foundation that the next generation, nor the next, nor the next after that will have to go to war to defend our freedom.”

2nd Lt. P J Ward’s wish for peace has been echoed through the years by all who have fought under that American flag. No one wishes for peace more, nor hates war more than the soldier or sailor who has suffered and endured the ravages of battle on behalf of his country.

After the war, P J Ward attended Georgia State University and graduated Cum Laude. He received his Masters Degree from Hofstra University of Long Island, New York and did graduate work at New York University in New York City. He worked as an Account Systems Analyst for the Atlantic Richfield Oil Company and also for the Alaska Pipeline Service Company. Ward’s wife, Claudia, died in 1972 when they were living in Jackson Heights, New York. Her funeral was held in Crestview, Florida with burial at Live Oak Park Cemetery. After his retirement, Ward moved to Century, Florida. He was elected to the Century City Council in 1977 and was serving on the council at the time of his death in 1987. He was first elected Mayor of Century in 1979 and re-elected in 1983.

He was a member of the National Association of Business Economists and the Northwest Florida Regional Planning Council. He served as President of the Panhandle League of Cities in 1986 and 1987. P J Ward died on October 9, 1987. His funeral was held at Flomaton Funeral Home Chapel in Flomaton, Alabama, with burial in the Smith Cemetery near Brooklyn, Alabama. He was survived by his brothers, Marvin I. Ward and Willie L. Ward, and his sister, Lucille Ward Odom.

John Vick

The author thanks Wyley Ward for his assistance in writing about his cousin, P J Ward.

[Sources: Wikipedia; 384thbombgroup.com; The American Air Museum in Britain; U.S Army Air Corps, missing aircrew report #16117; The Andalusia Star article May 27, 1943; The Andalusia Star article September 23, 1943; The Andalusia Star article June 4, 1945; The Pensacola News Journal obituary February 13, 1972; The Pensacola News-Journal obituary October 12, 1987]