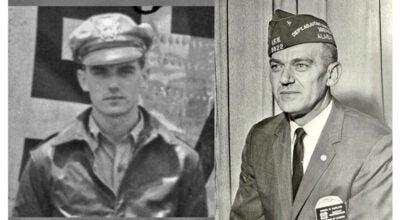

William Watts Avant, 1st Lieutenant, U.S Army Combat Engineer, WW II Veteran

Published 4:39 pm Friday, September 24, 2021

- 1st Lt. William W. [Bill] Avant, U.S. Army Combat Engineer, WW II [Photo: Caroline Avant McCall]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Bill Avant always wanted to fly. Ever since he had traveled to see the air shows in Birmingham, Alabama, in the late 1930s, he had wanted to be a pilot. Bill followed through with his desire to fly by studying aeronautical engineering at the University of Alabama. He was halfway through his senior year in 1943 when his advanced Army ROTC class was ordered to Officer Candidate School [OCS]. Upon learning that, Bill applied for the Aviation Cadet program. Unfortunately, he was turned down and told that he would have to go through OCS as an engineer. In a letter home to his mother, Bill wrote, “Well, I feel like my heart has been cut out…They said I couldn’t be accepted as a flying cadet because I was taking advanced ROTC.” By the end of WW II, Bill Avant had served 16 months in the European theater as an Army Combat Engineer.

William Watts Avant was born January 8, 1922 in Andalusia, Alabama. His parents were Laurin and Olive Elizabeth Crittenden Avant. He had an older brother Robert L. [Bubba], older sisters Mary Olive [Spec] and Celeste and was later joined by younger brother Max. Bill Avant attended Andalusia schools and graduated from Andalusia High School in 1940, the first graduating class in the school’s current location. He worked at the A & P grocery store part time during high school. He enrolled at the University of Alabama in the fall of 1940.

In August of 1943, Bill’s advanced Army ROTC class was sent to Fort McClellan, Alabama for processing before traveling to Fort Belvoir, Virginia by train. Bill completed OCS in January 1944. He was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant and ordered to Camp Shelby, Mississippi. On the way, he stopped by to visit his family in Andalusia. Bill related many years later in a letter, “During this visit home, Mother scratched ‘Lt. Avant, Feb. 6, 1944’ on the kitchen west window with her diamond ring. It’s still there after 63 years with other names of WW II and Vietnam time frames.”

At Camp Shelby, Bill was assigned to the 982nd Engineering Maintenance Company. He was given command of the Contact Platoon. He managed to take private flying lessons while there and applied for a transfer to the Aviation Cadet program again. In late February, Bill’s commanding officer told him that the transfer had been denied because the company had been placed on alert for overseas duty.

Bill’s company traveled to New York City for their departure for Europe in late August 1944. They left aboard the HMS Queen Elizabeth on August 27 and arrived in England on September 5. They were sent to Dorchester on September 24 in preparation for crossing the English Channel to France. They departed the port of Weymouth on September 28. The entire 982nd was loaded onto four Navy LCTs [Landing Craft Tank] and proceeded to Utah beach where they were put ashore. From the beach they made their way to Paris where they were stationed.

Paris had been liberated on August 25 so the city was not totally secure by the time of the arrival of the 982nd. In postwar letters, Bill mentioned that there were still a few German soldiers in the area and that they were bombed twice while they were there. The city was off-limits for Allied soldiers except those assigned there. In October, Bill learned that his brother, Max had been wounded near Aachen, Germany, and sent to a hospital in Paris. He was not able to locate the hospital but learned that Max had recovered.

We don’t have a record of all the work done by Bill’s platoon while in Paris. They were responsible for the gasoline pipelines running from Cherbourg to the front. In a postwar letter, Bill recalled one trip to the pipeline, “When we first made contact with the pipeline unit, the officer there recognized my southern voice and said that their Supply Sergeant was an Alabama guy. It turned out to be Homer T. Hart, manager of the A & P grocery store where I worked weekends during high school.”

In postwar correspondence, Sergeant Bob Fritz wrote that Bill had sent two men to St. Lo, in northwestern France to grind the valves on the big engines that ran the pumping stations. Bill’s work took him into several hot spots near the front. In a letter home written in January 1945, he talked about one trip into Belgium, “I was up in Belgium last month and the snow was three feet deep. On that trip our convoy got strafed and we lost one truck and a bomb went off about 80 yards from me that really gave me a jar….I didn’t get scared, the only thing we did was cuss the Germans and keep on going.”

Back in Paris, Bill mentioned going to hear the Glenn Miler orchestra. Glenn Miller had died in December 1944 when his plane disappeared on a flight from England to France. In a letter home, he talked about the equipment his platoon worked with, “I’m getting a lot of practical experience in engineer maintenance of heavy equipment and light equipment. I’ve also learned to operate everything the engineers have got…including tractors, tournapulls and cranes. You should see me on a D-7 cat dozer.”

In early March 1945, Bill’s unit moved from Paris to Bakel, Holland, by motor convoy. The 982nd was placed under the command of the British 2nd Army. Bill wrote home that he lived in the home of a Roman Catholic priest. He mentioned seeing dead cows in fields that had been killed by German mines. While in Holland, Bill was able to get a ride in a P-38 Army Air Force fighter. The Air Force called these piggy-back rides and Bill really enjoyed it. After a few weeks in Holland, the 982nd traveled by convoy at night into Germany. Bill mentioned that they arrived at Rees, Germany, on the Rhine River. The crossing of the Rhine at Rees began the Battle of the Rhineland. The engineers brought up pontoon boats to support a temporary bridge. Paratroopers and gliders were landed on the east bank before the bridge was used.

Bill’s unit arrived in Munster two days later and was given orders to join to 9th U.S. Army in the Ruhr Valley. On April 16, Bill was promoted to 1st Lieutenant. In late April, the 982nd moved further east to Oberg. As they moved on the roads and highways, they were confronted with masses of liberated people. Bill commented in a letter home, “I guess every nationality in the world is on the move up and down these roads…especially on the super-highway…They pull or move on everything you can think of, from wooden wagons to horseback.”

In a postwar letter, Bill mentioned a danger encountered by Jeep drivers in liberated areas. Some German civilians formed a terrorist group called the Werewolves. They were known to stretch a wire across a road, about the height of a Jeep’s windshield. The Jeep drivers countered this by welding an iron bar on the front of the Jeep that would contact the wire first. Bill’s unit did not come in contact with any wires.

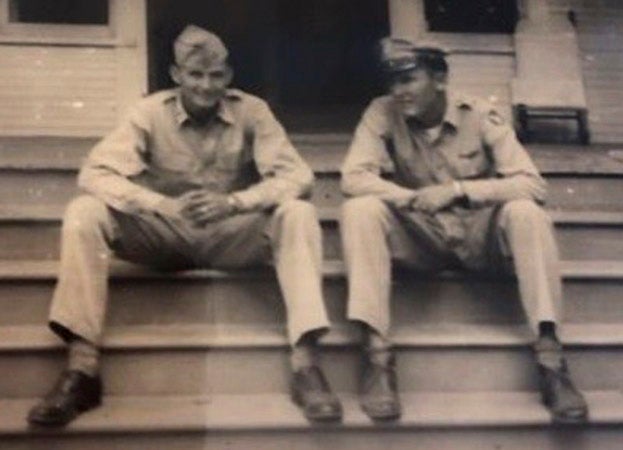

1st Lt. William W. [Bill] Avant in front of the jeep he drove more than 18,000 miles during his work as a Combat Engineer in

the European theater during WW II.

[Photo: Caroline Avant McCall]

The 982nd was sent back to Paris just before V-E Day. Bill arrived in Paris on May 6. He wrote, “After riding 350 miles on a train and then that much more on a truck, I got back to my outfit. My Paris pass was I guess the world’s best as you know V-E Day caught me in Paris.” Bill described a few of the things that happened, “Monday night, I went to the Folies Bergere and when I came out there was this good news that this thing was over with….Tuesday everything broke loose and I mean everything was wide open. You could get free meals every way…Tuesday afternoon was spent on the Champs-Elysees and there you could see everything. I’ve never seen so many people in my life.”

On May 23, Bill wrote, “I’ve put 18,542 miles on my jeep since I’ve been in Europe.” And he wasn’t finished. On June 4, he wrote that he was back in southern Germany near Frankfurt, in the town of Bingen. In late June, he returned to France. On June 20, he wrote, “I see America really gave ‘Ike’ a big welcome You know it’s hard to believe that I saluted his car up on the Autobahn, just above Frankfurt, not two weeks ago. I even got it returned too. He was in his big four door Cadillac.”

On July 7, Bill wrote that he and his brother Max had finally gotten together. “I found him about 14 miles from Paris and he came back here last night with us in the jeep…last night he and I sat be the Arc De Triomphe and talked for about an hour. I couldn’t hardly believe it.” On August 2, Bill wrote from Camp San Antonio near Paris, “I looked up Rebecca Darling [from Andalusia] on my way back from Rheims and was glad to see her. She’s the nicest thing I’ve seen in a year…. After I left her, I really got a bad case of the blues.”

1st Lieutenant Bill Avant celebrated V-J Day in southern France at Camp Calas, a staging area near Marseilles. He wrote his mother, “Well, I guess you all are really up in the air about V-J Day….I’m just waiting in a staging area and I’m wondering what the end of the war will have to do with us…there’s plenty of rumors we’ll go to the States…”

Laurin and Olive Avant had sent three sons to fight in WW II. Besides Bill, Robert L. [Bubba] served with the Army Air Corps in the South Pacific and Max served with the 9th Infantry Division in Europe. Max landed on Utah Beach on D-Day and fought on into Germany where he was wounded at Aachen, Germany.

With the end of the war, the 982nd was embarked aboard the SS General Richardson and arrived 10 days later on November 11 at Boston, Massachusetts. Bill was assigned to Camp Gruber in Muskogee, Oklahoma. The 982nd was disbanded on November 15. Later that month, Bill was transferred to the 1159th Engineering Combat Group at Camp Gruber.

In December, Bill met Patricia Ann [Patty] Guinn, who was a senior at Northeastern State University at Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Patty was from Arizona and was studying chemistry. After a brief romance, Bill and Patty were married in January 1946. Bill’s parents, Laurin and Olive flew to Oklahoma for the wedding.

Camp Gruber closed in February 1946 and Bill was transferred to Camp White, Oregon. It was decided that Patty would stay in Tahlequah and finish her degree. In April, Bill was transferred to Fort Lewis, Washington for separation from the Army which happened on April 21. Patty received her degree in May 1946. She and Bill then moved to Tuscaloosa where Bill received his degree in Aeronautical Engineering in 1947.

Bill accepted a job with North American Aviation in Los Angeles, California, after graduation. He worked with the supersonic wind tunnel for three years. He and Patty then moved to Mesa, Arizona, in 1951, where he worked with American Helicopter Company for two years. He then joined AiResearch Manufacturing Company, located near Phoenix, where he worked the next 31 years. Bill worked his way up from Development Engineer to Assistant Project Engineer and Engineer Specialist , Sr. He then transferred to the Sales Department where worked as Sales Engineer, Sr. until his retirement in 1984. All of Bill’s work was the pneumatic systems product line. During that time, he was awarded three patents. Patty died in 1967 and Bill married Teresa Kuhnlein in 1973.

Bill had gotten his private pilot’s license in 1946 and flying became his main hobby for many years. He owned three different airplanes including a Cessna Skylane 182 for 26 years. He flew all over the country and in Mexico. His favorite flight was to Oshkosh, Wisconsin, for their annual fly-in. He wrote that his total Log Book flight time was 1,747.68 hours.

Bill and Teresa moved back home to Alabama and the Avant home in 1984 and formed the Avant-Crittenden Timberlands, which Bill managed. They renovated the home and it was placed on the Register of Historic Places in 1996. Bill and Teresa traveled extensively until her death in 2009. Bill died in 2011 in the Avant home. He had said that, “I’m going to take my last breath where I took my first.”

John Vick

[The author would like to thank Caroline Avant McCall, the daughter of Bill Avant, for her help in writing the tribute for her father]

More COLUMN -- FEATURE SPOT