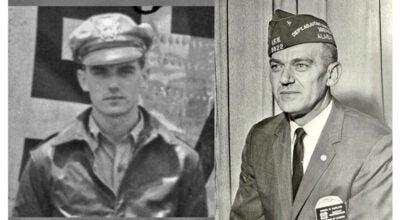

Wesley E. Courson, 2nd Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Force, WWII Prisoner of War

Published 4:29 pm Friday, July 23, 2021

- Aviation Cadet Wesley E. Courson, Photo in an AT6 Trainer sent to his mother. PHOTO: Marc Kyzar

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Part 1 – Five Missions Over Germany

Author’s note: The author wishes to thank Mrs. Mary Courson Kyzar and her son, Marc, for providing a copy of her brother’s WW II wartime diary. Mary’s brother, Wesley Courson, was a B-17 pilot during the war and was shot down on July 26, 1943. He would spend the remainder of the war in a German prison camp. He kept a meticulous diary covering his experiences.

Wesley Eugene Courson was born February 24, 1922 in Andalusia, Covington County, Alabama. His parents were Luther Eugene Courson and Lena Tollison Courson. Two younger sisters were born later, Lois and Mary. Wesley attended Andalusia public schools, graduating from Andalusia High School in 1940. He worked briefly at the Alabama Textile Products [Alatex] plant before enlisting in the Army in June 1941.

After basic training, Courson was trained as an aircraft mechanic at several bases. During that time, he applied for flight school and was accepted. Upon completion of basic, primary and advanced flight training, Courson was given his pilot’s wings and commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant. He was sent to Hendricks Field at Sebring, Florida, where he trained to fly the B-17 bomber. Learning to fly the B-17 took him all across the country for several months. In May 1943, he was given a crew and orders to prepare for a transatlantic flight to England.

B-17 Flying Fortress, the type bomber flown by 2nd Lt. Wesley E. Courson during WW II.

PHOTO: aviationhistory.com

Upon landing in England, Courson and his crew were assigned to the 306th Bomb Group, 423rd Bombing Squadron. Their first four flights into combat were fairly routine with only minor damage to their aircraft. Their 5th mission began on the morning of July 26, 1943. Courson would recall later,

“Our fifth mission proved to be the most and the worst. More flak and fighter planes than all previous runs together. Higher altitude mission at 27,500 ft. for it was a hot spot we were hitting that day. The submarine depot and repair installations in Hanover, Germany.” That mission for Courson and his B-17 crew proved to be their last of the war.

As their B-17 neared the target, Courson and his co-pilot, Lt. Bronson, struggled to maintain control. In his diary, Courson described their dire situation, “The flak looked like black clouds….suddenly, there was a resounding explosion just beneath us. The sound and the pressure hit our ears simultaneously and lifted the plane with a jar. Immediately, the four superchargers went wild…I had absolutely no control of manifold pressure…any attempt at changing the prop pitch setting [with the thought of feathering engines one and four] set up such vibration that it was beyond structural safety. Fighting to hold in formation, Bronson and myself were soaked in perspiration…..The bomb run to the target was an eternity. When the bombardier, Lt. Lynch, let the 6,000 lb. load go, we shot up 200 ft.”

Still trying to maintain their place in the formation, both pilots were fighting the controls to maintain altitude. About that time, the formation turned left and lowered their altitude for the return trip to England. That maneuver brought more trouble for Courson’s plane. “We tried to come on down with them but our flaps began to rip off and lose their effect.” Losing their ability to stay within the formation made them a target of the German fighter planes. “They had spotted us as a cripple and were moving in for the kill. Most of the fighters were FW-190s…they were coming in fast and hitting hard…The tail-gunner called in all shook-up…the best I could understand was that the barrels of his guns had been shot off….It happened faster and faster…I saw the top of the left wing open up with at least four gaping holes….The right waist gunner called and said the 1st radio engineer was on the radio-room floor…his whole head is blown off.” About that time the right waist gunner was hit. Courson called for the tail gunner to take over the waist gun. “ I couldn’t spare the co-pilot because he had his feet against the control column to hold it forward. Without that, I couldn’t hold against the forces. I also wanted the other officers and men to stay at their guns and keep them hot.”

The gunners were calling out hits and claiming some kills. Courson couldn’t verify any kills because of the confusion. Courson was suddenly jarred by an explosion, “I heard the high-pitched bang of a 20mm round at the same time the hot concussion hit the back of my head. I looked back to see the 1st engineer fall out of the top turret. I had to also look at his handsome face that was now spurting blood from his eyes and cheeks…But he got off the floor saying something about the plexiglass dome blowing up in his face…I yelled to him to get his parachute adjusted and stay where I could yell to him. The 1st engineer asked Courson about his parachute which was located on the top step of the catwalk. He retrieved it and helped Courson strap it on. Courson noted, “That action on his part may well be the reason that I was later able to get out of the aircraft.”

The fighters were still pressing home their attack. “They were coming in lined-up three to five in a row and their leading edges looked like a fireworks display….the number three engine showed fire…we tried to blow CO2 but nothing came out…number two engine was mostly oil and smoke…the acrid stench of burn was everywhere. I looked back to see what was causing it and I still don’t know what could have set the entire floor of the radio room on fire… The tops of both wings had been chewed up by 20mm fire…The trailing edge of the left wing was ragged and a large piece flapped a couple of times then blew away…So this was the way it was…no way to move…no way to go but down.”

With the intercom gone, Courson yelled to the Engineer, “Champ, it’s time to go. I’ll be giving the three bell rings continuously but yell to everyone to bail out….we can’t let go of the controls so tell them to throw anyone on the floor out and hold onto their ripcords. That was the last thing I knew about what went on in the back.”

Courson instructed the Bombardier to destroy the Norden bombsight. He recalled, “I could hear the .45 caliber as Lynch shot up the bombsight and what sounded like everything else in the nose. If the Germans hadn’t shot us down by then he would have done it for them.” It was now time for Courson and Bronson to bail out. The Co-pilot went first. Fearing that the plane would fall off to the left and go into a spin once he let go of the controls, Courson decided to open the bomb-bay doors, “That was the biggest hole I could think of to go through. I didn’t know the door controls and locks had been shot away and that they would be slamming open and shut in the wind and they were very heavy doors.” He decided to risk it anyway and jump when the doors offered an opening. As he jumped, the plane did a sharp roll that caused him to be struck as he went through the doors.

Courson recalled, “They knocked the living hell out of me. I knew I was hurt and I knew I was falling. There was lots of wind flurry and whistling sounds and body numbness that had pain mixed with it. I fell forever. When the parachute caught the wind in a jolting wallop it knocked me out cold. At some point I became aware that I was being escorted down by two circling FW-190s. I could see the earth looming larger…it met me hard and didn’t give an inch. I am lucky to have come through that beating with only a dislocated right knee, torn lateral ligaments in that area, and possibly a hairline crack in the pelvic region.” As Courson lay there in confusion, still in lots of pain, he noticed a man standing nearby. Courson remembered the man saying “Netherlands,” which gave him some hope. That hope was short-lived when five German Border Guards arrived. End Part 1

[To be continued]

— John Vick

More COLUMN -- FEATURE SPOT