Flying the Hump with Dempsey P. Albritton, 1st Lt., U.S. Army Air Force, WWII

Published 1:37 pm Friday, July 2, 2021

- Dempsey [second from right standing] and pilots in Brownsville, Texas.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Books and movies tell about the Allied war effort during WW II to fly supplies over the eastern Himalayas to the Nationalists Chinese Army fighting the Japanese. The U.S. 14th Air Force and the China Air Task Force had been effective at fighting the Japanese occupation of China. The Allies realized that Japanese troops fighting in China couldn’t be used to fight in the South Pacific. When the ground supply route known as The Burma Road was lost to the Japanese in 1942, a new supply line was established through the air. The new route from bases in India across the Himalayas to Kunming in China was dubbed, The Hump.

With few navigational aids, the mission of flying The Hump was one of the most dangerous routes flown by the Army Air Corps in WW II. The terrain flown reached heights of more than 20,000 feet. The weather was notoriously treacherous with winds aloft often exceeding 100 mile-per-hour and monsoon-like rains intermingled with zero-visibility fog. In December 1943, a “no weather” proclamation was issued – The Hump is never closed. Besides the dangers of the Himalayan geography and weather conditions, Allied flyers had to worry about the many Japanese fighter planes waiting to pick off the slow-moving transports.

The airlift of supplies was put under the Air Transport Command which flew several aircraft but predominantly the C-46, C-47 and the C-54. By the end of the war, the ATC was flying more than 722 aircraft, maintained and flown by more than 84,000 personnel, which included 4,400 pilots. They had delivered more than 650,000 tons of materiel over their 42 months of operations. They did so at a terrible cost. Not all crashes were recorded but it was estimated that the ATC lost more than 590 aircraft along with1,314 crew. Some 1,171 men survived crashes and returned to safety and more than 345 men were declared missing.

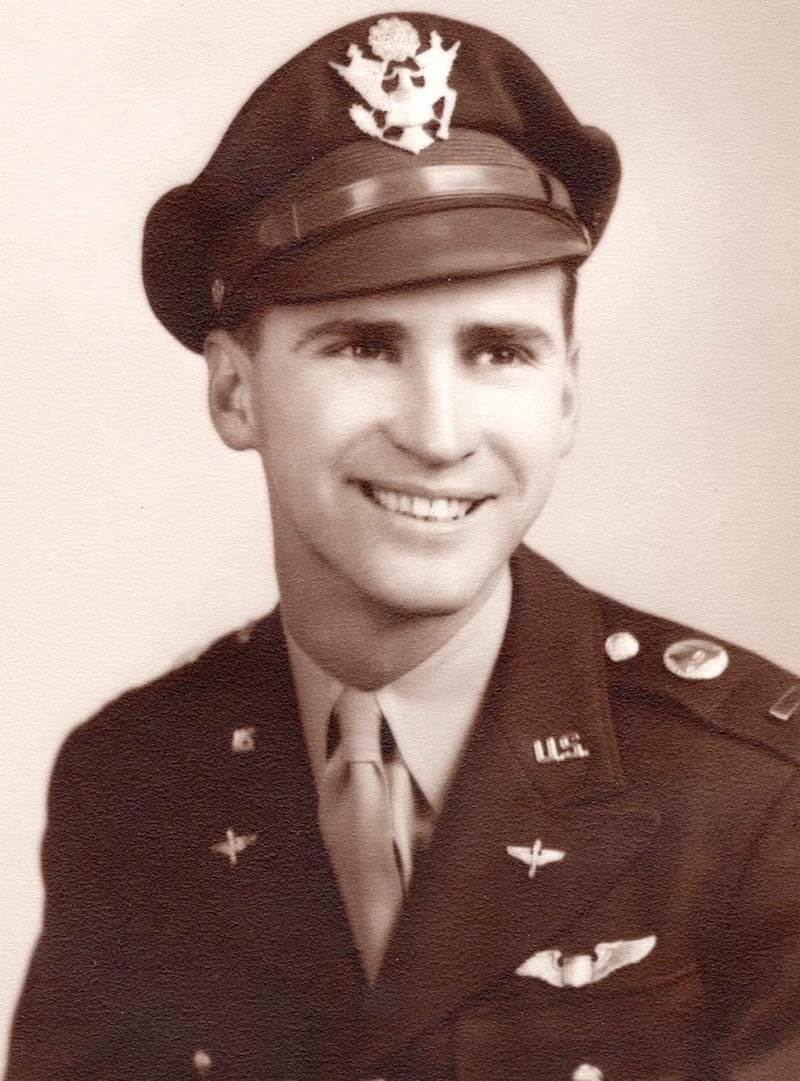

Into this perilous wartime operation stepped a daring young C-46 pilot from Andalusia, Alabama named Dempsey Albritton. When the operation ended he had heroically completed more than 91 missions safely.

Dempsey Powell Albritton was born August 20, 1920 in Andalusia. He was the 10th child of William Harold and Annie Rebecca Mashburn Albritton. He was named for Dempsey Powell who had been a partner with Edgar Thomas Albritton in the law firm of Powell and Albritton. Dempsey grew up on what is now called Albritton Road but was originally called Troy Street. His father died when he was eight years old and Dempsey grew up with a close relationship to his older brothers, especially Robert Bynum and William Harold, Jr. That relationship remained close throughout the rest of his life.

Dempsey graduated from Andalusia High School in 1938, the same year that the original Albritton home was destroyed by fire. He lived for a time with his brother Jesse in Montgomery before joining the Army. He was assigned to the Headquarters Battery, 1st Battalion, 117th Field Artillery at Camp Blanding, Florida for basic training. After completion, he was sent to Camp Bowie for advanced training.

While at Camp Bowie, Dempsey took an exam to become an Aviation Cadet. The potential ACs were sent to Waco Army Flying School at Waco, Texas. The Army Air Corps established the Aviation Cadet program to augment the number of aviators being trained to fly. Prior to this, only college educated men were accepted. Upon completion of the AC program, Dempsey would receive his wings and a commission as a 2nd Lieutenant.

Primary training was done at Mira-Loma Flight Academy near Oxnard, California. Dempsey noted that he had completed 60 hours flight time in the AT6 training aircraft when he had finished primary. His letters home note that he trained at the West Coast Training Center at Oxnard and Santa Ana Army Air Base at Santa Ana, California. After primary was finished, he was sent to Luke Field, Arizona for basic and advanced training.

In his letters from Luke Field, Dempsey said that he had completed ground school and was into every phase of flying. He noted, “I have a little English RAF [Royal Air Force] pilot for an instructor and he is a swell fellow.” In one of his mother’s letters, she must have asked about a crash. He responded, “You asked me about cracking up. It was only a ground loop [which is quite common around here] and it didn’t even shake me up.”

[Author’s note: Ground loops were common during training. They can happen when the tail of the plane gets off-center of the landing direction causing one wing to lift and the other wing to drop sometimes hitting the ground. In extreme cases, the aircraft becomes unstable and flips upside down].

Dempsey’s letters do not offer much detail about the training at Luke. He mentions gunnery school and flying at night. At some point he transitioned to multi-engine aircraft because most of his flying in the war involved transport planes. Upon graduating at Luke Field, he became a pilot and was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant and sent to the Ferrying Division of the Army Transport Command.

From Brownsville, Dempsey flew C-47s to the Panama Canal Zone. In a letter home he said, “I just got back from a trip south. Seems kind of funny to sleep in a little shack in the jungle one night and in a nice hotel back in the States the next.” They stopped in several Central American countries but he couldn’t mention the names because of secrecy.

Dempsey would be stationed at Rosecrans Field near St. Joseph, Missouri for a time and then Romulus Field, Michigan. He ferried planes around the country from those bases. He also got checked out in single engine fighters and P-38 fighter/bombers at Palm Springs, California. He ferried those planes throughout the continental U.S.

The scope of his job got bigger after that. He ferried B-25s to Corsica, Tunis and other points in North Africa by way of the South Atlantic Route. On a mission from England early on the morning of June 6, 1944, Dempsey flew a B-17 to the U.S. by way of North Africa. Only after landing did he find out about the D-Day invasion.

In September 1944, Dempsey was sent to Mohanbari Airfield in India. The airfield was home to the 1332 Army Air Force Base Unit. Flying out of Mohanbari, Dempsey would go on to complete 91 Hump missions.

It was common for air crews staying in India to hire young teenagers to do chores around their living area. These helpers were called “houseboys, a slang term borrowed from the British. After the war, Dempsey often talked about the young man that worked for them in India. Dempsey was not accustomed to having someone do laundry, clean-up, shine shoes and run errands. Dempsey really appreciated the young man’s help because he had grown up with older siblings and had often been their “houseboy.” There’s not much correspondence from Dempsey during his time “flying the Hump.” Sometime after the war, he recalled one scary incident that happened on a return flight from China. They were totally socked in by the weather at Mohanbari. Nearing the home airfield, they ran out of fuel and started gliding through the clouds, when suddenly, they broke out of the clouds and saw the airfield, dead ahead.

In one of his last letters to his sister, Margaret [Monnie], he talked about one of his last missions, “Went up to Agra to pick up a ship and had to wait six days on it…… On the way back, I made a couple of pictures of the Taj Mahal. From the air they aren’t so good because I was trying to fly and take pictures at the same time.”

Dempsey returned to the States in April 1945 and was briefly stationed at Love Field in Dallas, Texas, ferrying A-26 aircraft. After that he was sent to Rosecrans Field where he served with MATS [Military Air Transport Service] under the command of Lt. Col. Martin Peterson, his former chief pilot at Mohanbari. He left the service and returned home in December 1945.

After returning to Andalusia, Dempsey worked at several jobs. He taught flying lessons for a while and worked as a crop duster. His brother, John Thomas [J T] started an oil dealership with Gulf Oil Company in the 1950s. After working with J T for a while, Dempsey started his own dealership in Brewton, Alabama in 1959. He met and married Lucille Martin from Castleberry, Alabama in 1961. J T had introduced Dempsey to Lucille who had been working as a secretary at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama. They had a son, John Albritton who was born March 24, 1964. He currently resides in Brewton.

Dempsey P. Albritton died July 8, 2004 at age 83. He was buried at Andalusia Memorial Cemetery in Andalusia, Alabama. Lucille Martin Albritton died May 26, 2021 and was buried alongside her husband.

— John Vick

[Sources: Wikipedia; “Flying the Hump During World War II,” Lyon Air Museum; We Are the Mighty blog]

The author would like to thank Dr. Bill Albritton and John Albritton, Dempsey’s son, for their help in writing about Dempsey Albritton. All photos are courtesy of the Albritton family.

More COLUMN -- FEATURE SPOT