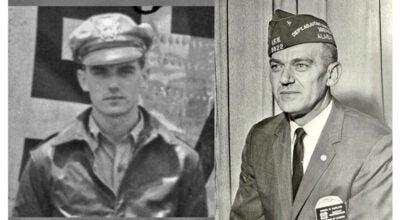

COLUMN: James Richard Smith Sr., FN1, U.S. Navy, WWII Navy Veteran

Published 3:00 pm Friday, January 17, 2025

- A spry looking 95 year old James R Smith, Sr. The chest to his right, was made for him at Olongapo, Philippines in 1945. (PHOTOS PROVIDED)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

(Author’s Note: We are sad to report the death of another member of The Greatest Generation, Mr. James Richard Smith Sr. of Andalusia, on Jan. 13. This article was written five years ago when Mr. Smith was a spry 95-years old. At the time of his death, James and Mrs. Smith had been married 77 years. — John Vick)

James R Smith, Sr. was born Oct 18, 1924 in McKenzie, AL. His parents were Calvin and Annie Smith. James attended the old Shreve School until the 6th grade. For several years, he worked farming jobs at a young age. When he turned 17, he went to Evergreen and joined the Civilian Conservation Corps. The CCC was a work relief program established by President Roosevelt, that employed millions of young men in various environmental projects. Over the years that the CCC operated, more than 3 billion trees were planted and many trails and shelters were constructed in more than 800 parks nationwide. Our own Open Pond area had much work done by the CCC.

James said that his primary work involved spraying kudzu. At some point, the Evergreen unit was split and James, along with others, was sent to Robertsdale to fight forest fires. In early 1941, he left the CCC and tried to farm. After farming about a year, he went to Pensacola and joined Hardaway Construction Co. A year later, he received his draft notice in 1943. When he reported to the induction center at Ft. McClellan, AL, he was given a choice of services and he chose the Navy. After being sworn in, James made an allotment for his Navy pay, giving his mother $50., which the Navy matched. The next day he reported to Pensacola, FL.

Basic training was done at Bronson Field, located not far from Saufley Field in Escambia County, FL. After basic, James was sent to Barin Field, AL., where he joined VT-4 [Navy flight training squadron 4]. He went through a 7-week school in aviation maintenance and was trained as a plane captain, responsible for the readiness of the plane when the pilot was scheduled to fly. The aircraft was the Navy SNJ training aircraft. Barin Field acquired the descriptive nickname, “Bloody Barin”, because of the high number of fatal crashes by the young pilots in training. He remained at Barin for several months. James recalled that once he went to visit his brother, Leroy, who lived in Pensacola. A stranger opened the door at the home and told him that his brother had moved to Atmore. Communication in the 1940s was a little slower than now.

In March 1944, James was ordered to Norfolk, VA., where he joined the U. S. Naval Landing Force Equipment Depot. As a part of the deck force, he loaded ships, cleaned, painted and similar work. He recalled, when driving around Norfolk, signs in yards saying, “Sailors and Dogs Keep off the Grass”. He was there for about six months.

From Norfolk, James joined a troop train that carried sailors across the country to San Bruno, Ca. They arrived at the Navy Advanced Base Personnel Depot on Oct 24, 1944. There, they underwent combat training. James’ unit was housed in what had been an old horse racing track. Some lived in barracks on the track, while others were housed in remodeled horse stalls. Later in the war, many Japanese Americans were relocated there.

When they arrived in San Bruno, the troop’s Navy blue and white uniforms, along with their shiny black shoes, were taken and shipped back home. In their place, they were issued dark green clothing, similar to those worn by Navy SeaBees. They were also given helmets, pith helmets, back packs and a rifle. Every sixth man or so got a machete.

After about a month, they were given a 10-day pre-embarkation pass. James was unable to go home because of the distance. After that, they reported to Treasure Island, Ca., for overseas processing.

On Dec. 26, 1944, they boarded the SS Exeria, a United Fruit Co. ship that had been converted to a troop transport. They departed for an unknown destination on Dec. 30, 1944, without a convoy. They were told that the ship’s speed of 21 knots could outrun any submarine.

The Exeria arrived at Pearl Harbor on Jan. 5, 1945. On Jan. 10, they left Pearl Harbor for Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands. They arrived about a week later. Eniwetok was a central supply depot for all U.S. forces fighting in that part of the south Pacific. James said, “I was surprised Eniwetok didn’t sink into the sea from the mountains of supplies that had been stored there”. The men from his ship returned with cans of peaches that had been “appropriated” from the stacked cases of supplies. James always remembered that can of peaches.

When the Exeria left on Jan. 19, it was accompanied by a large convoy which included Six Navy destroyers. It was rumored that they were bound for the Lingayen Gulf in the Philippines. Neither James nor his buddies had any idea where that was located.

In the tropical waters of the Pacific, the ship’s interior quarters became unbearably hot. Most of the men tried to sleep topside on the deck, using their Mae West life jackets as a pillow.

The convoy arrived somewhere in Leyte on Jan. 25. They had been diverted from the Lingayen Gulf because the landings there had gone better than expected. The next day, they left for Subic Bay, Philippines, but didn’t arrive until Feb. 2.

As they approached Grande island, which sat at the entrance to Subic Bay, a small tugboat pulled back a submarine net so that they could enter. James wondered how the U.S. could have captured an intact Japanese submarine net so quickly after the battle. Olongapo, where they were to report, was not captured until Jan. 30, just a few days before their arrival.

Because the bay was so shallow, the men had to disembark by crawling down cargo nets on the side of the ship, into small landing craft. The men from the ship were fed from a field kitchen that had been set up. The Filipino children could be seen scavenging scraps from the field kitchen’s garbage cans.

James Smith’s job entailed driving a 2.5-ton truck [called a deuce and a half], filled with gravel. He also made trips to Manila, about 80 miles away, to bring back rice to feed the starving Filipinos.

One such trip was memorable for Smith, because of a close call. The mountainous road from Olongapo to Manila had recently been captured from the Japanese at a very heavy cost in lives from both sides. The road was called Route 7 or Zig Zag Pass.

James noted that the remnants from the battle were still visible along the sides of the dangerous road, including weapons, ammunition and dead Japanese. He recalled that the smell was horrendous. On one particular trip, James was accompanied by 5 or 6 Filipinos who were to help load and unload the rice. The road only allowed for a very slow speed, and at some point, the Filipinos spotted a Japanese patrol and promptly bailed out of the truck. James did not notice that they were missing until he got back to the base at Olongapo and realized what had happened. The rains were constant and James remembered staying wet continuously because of the leaking tents.

During the time he was assigned to the motor pool, James received word that his 16-year old sister had died. James approached a Chaplain and explained that his sister had died. The Chaplain said, “Son, don’t you know that there us a war going on”. James knew right then that he couldn’t go home.

By Oct 1945, with the war over, James had hoped he had enough “points accumulated” to go home. The points were based upon your length of service, your time overseas, combat awards and number of dependent children. James was in the second round going home. In Dec. 1945, he received orders to board the USS Tazewell for the long trip back to the States. The return trip was hazardous because they ran into a typhoon. Several ships were lost, but the Tazewell survived and made it back to Treasure Island. From there, James was sent by train to a Navy Separation Center in New Orleans, where he was discharged. On Jan. 13., 1946, James caught a Greyhound bus to Crestview, Fl., where his sister, Bertha lived.

James Richard Smith had served two years, five months and 17 days. He started his Navy service as a Seaman Apprentice [SA] and was discharged as Fireman First Class [FN1].

He received the Asiatic Pacific Area Campaign Ribbon, the Philippine Liberation Ribbon and the WW II Victory Medal.

James and Evelyn Teat were Married in 1947.

After that, he went to school in Baker, Fl., for a while but left and briefly lived and worked in McKenzie, Evergreen and Mobile. where he worked for International Paper Co.

In 1950, he enrolled at Red Level High School where he graduated a year later through an accelerated program. After that, he attended the county school for returning veterans located on Oak St. in Andalusia].

He studied accounting under Mr. Patterson. He also joined the Navy Reserves in 1950.

His first job after accounting school was with Reynolds Home Furnishings in Flomaton, Al.

In 1952, James went to work at Brookley Field in Mobile, doing warehouse work. In 1955, his Navy enlistment ended and he joined the US Air Force Reserve as a Tech-Sgt. [ E-7]. He moved to Bates Field from Brookley in 1955. He worked as the base equipment manager at Bates until it was closed in 1966, when he moved back to Brookley. He was the Allocation Officer for a squadron of C-119 Air Force transports ,called the Flying Boxcar. While at Bates Field, James was put on active duty in the fall of 1962, during the Cuban Missile crisis. He recalled that he and a crew of men spent a day and night in a C-119, ready to leave at a moment’s notice.

When Brookley Field closed in late 1966, James and his family moved to Ozark, Al., where he worked at Ft. Rucker with base services, such as golf courses, parks etc. He had transferred back to the Navy Reserves which met in Pensacola. He attained the rate of Senior Chief Storekeeper [SKCS] [E-8] in 1981, after returning to active duty, as explained below.

At one of the Navy Reserve meetings, James met a Navy Captain who was the Commander of the New Orleans Naval Reserve District. The Captain asked him if he would be willing to return to active duty to take over the District Accounting Office for the New Orleans District. James saw the chance to raise his pay and further his retirement income, so he took the job after resigning from his job at Ft. Rucker. He and the family moved to an apartment on the west bank of the Mississippi River in New Orleans [they still owned a permanent home in Andalusia that they had bought in 1968].

In 1984, James retired from active duty in the Navy as a Senior Chief Storekeeper [SKCS], with a rate of Senior Chief Petty Officer. From his enlistment in 1943 until his retirement in 1984, he had been in the military, either reserve or active duty for 41 years.

They moved their family back to Andalusia where he and Evelyn still reside. They have two children; James Richard, Jr. of Andalusia and Sheila Arlene [Rinkey, Sr.] Stanley of Opp. They also have two grandchildren, Mathew Stanley and Rinkey Stanley, Jr. of Dothan.

John Vick

More COLUMN -- FEATURE SPOT