Mission Over Munich – November 16, 1944 Samuel Marlin Hamilton, First Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Force – WW II Conclusion

Published 1:00 pm Friday, December 29, 2023

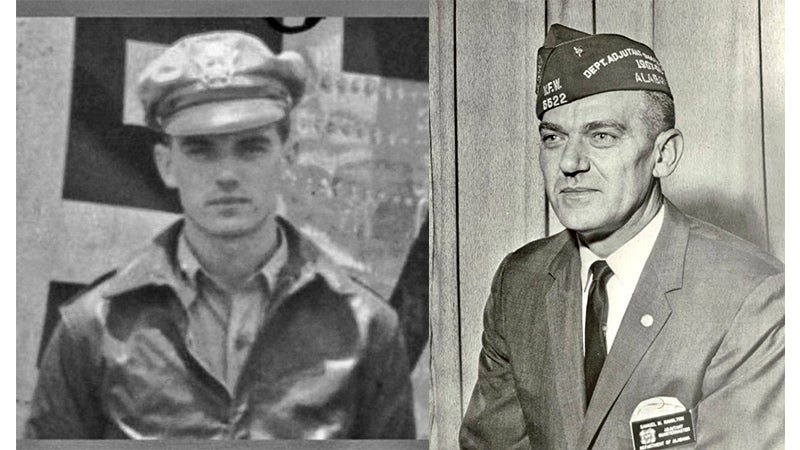

- LEFT: 1st Lt. Sam Hamilton, B-24 bomber pilot, in WW II Army Air Force Uniform. [Photo: Jim Lawrence] RIGHT: Hamilton was a lifetime member of the Opp VFW, Post 6622 and Adjutant General of the Alabama VFW for 20 years. [Photo: Jim Lawrence]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The first combat mission for Sam Hamilton and his crew began early in the morning on November 11, with a 6:30 a.m. breakfast followed by a briefing for the day’s flight. Most men ate a light breakfast, but for some it was just coffee. The first combat flight brought on butterflies for most flyers. A mixture of butterflies and thoughts about the cold, bumpy flight ahead, made many appetites disappear. The last thing an airman needed was to throw-up in his oxygen mask at 25,000 feet.

Crash site of White L For Love located about 12.4 miles north of Salzburg, Austria. [Photo: Luftwaffe Records]

The target for their first mission was the Sauerwork Ordnance Depot in Vienna, Austria. The after-mission report mentioned IAH flak [intense, accurate and heavy]. Once they were back on the ground, the crew counted 30 holes from flak in their bomber. Luckily, no one had been injured.

After a day off, they flew their second mission, bombing factories and warehouses at Banhida, Hungary, near the Yugoslavian border. All 35 aircraft returned from the mission.

Hamilton and his crew would fly an additional seven missions before their ill-fated flight to bomb Munich on November 16. Those missions included flights to Graz, Austria, to bomb the Neudorf Aircraft Engine Factory; the railroad marshalling yards at Maribor, Yugoslavia; the railroad marshaling yards at Rosenheim, Germany; the railroad marshalling yards, Augsburg, Germany; and the M.A.N. Diesel Submarine Engine Factory; Vienna, Austria. Their eighth mission to Linz, Austria, to bomb the Floridsdorf Oil Refinery was aborted due to weather conditions. Their ninth mission, their last before Munich, was to bomb the Linz Benzol plant at Linz, Austria.Sam Hamilton had just been promoted to 1st Lt. a few days before the flight on November 16, 1944. The events leading up to White L’s loss were described in Part 1 published in the December 23 edition of the Andalusia Star-News.

The crew makeup for the November 16th mission would be different. Sam Hamilton would fly as the co-pilot, allowing pilot Captain Clifford W. Stone to complete his 50th mission, earning him a trip back to the States. There were a couple of other crew member changes also: Dana Satterfield would not fly that day because his turret was occupied by a new radar ray-dome. Joe Rudolph was not aboard because Hamilton was taking his place. John Murphy was replaced by Arthur Godar as bombardier, probably because of his experience with the new radar.

Sam Hamilton described the sudden sink he felt as the plane lost airspeed from 180-190 mph to 145-150 mph. The plane suddenly went into a steep dive of almost two miles before Stone and Hamilton were able to regain control. It took tremendous effort by both men, with their feet on the rudder pedals and both men pulling back the yokes. During the dive, the crew members in the back were tossed around and pinned to bulkheads.

With White L out of formation and rapidly losing altitude, Captain Stone had the crew jettison all loose equipment through the opened nose wheel door. They also had to destroy the secret Norden bombsight and the new radar ray-dome before throwing them out.

As the plane continued to lose altitude, it was attacked by two waves of German fighters. Captain Stone realized that it was unlikely that he would be able to successfully ditch the plane but he still asked the navigator for a course toward Vienna and the Russian lines.

Bronze plaque [in downtown Opp] honoring Marlin Hamilton for his work to preserve Opp’s original lamp posts. [Photo: Jim Lawrence]

All of the crew made it safely to the ground and were soon captured. Sam Hamilton said that all eleven men survived the parachute jump but that six were injured and one was killed during the capture. Captured American flyers were usually treated better by German soldiers than civilians who held a pent-up anger from the bombings. Records later indicated that Lt. Morris “Maury” Caust [ a crewman on the White L that day] was shot and killed by a young German civilian while being told to surrender.

The phrase most often heard by captured Americans was, “Fur Sie ist der Kreig vorbei,” which translates to, “For you the war is over.” The young men who flew White L now began a new phase in their life – that of being a prisoner of war. Their families at home would receive a telegram notifying them that their service member was “missing in action.” In some cases, it would be months before they received a second telegram notifying them that the family service member was alive and a being held in a German prison camp.

The captured crew members were first taken to a farmhouse near Lamprechtshausen, Austria. From there, they were taken to Gestapo Headquarters in Salzburg for interrogation. The town of Salzburg had suffered repeated bombings by B-24s and the townspeople were angry when they saw an American flyer.Around November 22, Hamilton and his crew were taken for further interrogation to Dulag Luft 1, located at Oberursel, some 30 miles northwest of Frankfurt. A Dulag was an entrance camp where prisoners were interrogated before being sent to a permanent Stalag Luft [Luftwaffe prison of war camp]. The food was meager, with breakfast consisting of a couple of slices of bread with jam along with a coffee substitute. Dinner was two more slices of bread, along with water.

During interrogation, the men were held in isolation for several days [in some cases a month]. They were denied cigarettes and Red Cross parcels. They were questioned once or twice a day by the Gestapo, who slapped some POWs and threatened others with death when information was not forthcoming.

In late November, the enlisted crewman from White L were taken to Stalag Luft IV while the officers were sent to Stalag Luft I, located near Barth, Germany. There was another flyer from Opp, Alabama, who was sent to Stalag Luft I around the same time as Hamilton. Sgt. Wilbur R. Jernigan had been a waist gunner on a B-17 bomber that was shot down on November 7, 1944, and subsequently sent to Stalag Luft I.

One of America’s greatest fighter group commanders was also a prisoner there. Col. Hubert “Hub” Zemke had been commander of the 56th Fighter Group [called The Wolfpack] which was credited with 665 air-to-air victories, more than any other fighter group in the European Theater. He was the senior Allied prisoner at Stalag Luft I.

The Food at Stalag Luft I was worse than at the holding camp. Hamilton and Jernigan recalled that most of the potatoes were rotten, sometimes containing insects or worms. The bread was stale and not available every day. Fortunately, their stay would come to an end on May 1, when the camp was liberated by the Russian Army.

Things could have gone a lot worse when the camp was liberated. Toward the end of April, the camp commandant, Oberst Gustav Warnstedt, met with the ranking Allied officer, Col. Zemke. Fearing the approaching Russian Army, he informed Zemke that he intended to have the prisoners march some 150 miles to a location near Hamburg. Zemke took a vote of the prisoners and they voted to refuse to march. Zemke reported back to the camp commandant that the prisoners would not leave. He backed up his statement by saying that if the Germans tried to force the men to march, the prisoners had a secret commando unit that would storm the guards and take over the camp.

Zemke was able to convince the commandant that leaving the prisoners behind would prevent bloodshed. When the Russians arrived on the morning of May 1, the German guards had left the night before.

After they had made contact with Allied soldiers, Hamilton and Jernigan were sent to Camp Lucky Strike in France, in preparation for their return to the States. Sam Hamilton was promoted to Captain and had been awarded the Purple Heart, the Air Medal, the Italian Campaign Medal and the Distinguished Service Cross.

After arriving back home, Hamilton enrolled at the University of Alabama and completed the requirements for a degree in Geology in December 1948. He returned to Opp and was involved in several businesses before selling out in 1960. Hamilton may have retired from business but he remained active in numerous activities. He taught mathematics at the MacArthur Campus in Opp of what is now LBW Community College until 1982. He was active in helping veterans who were getting an education through the GI Bill. He also taught night classes to veterans and adults who were getting ready to re-enter school. He was a member of the Opp Lions Club, and a lifetime member of the Opp Post 6622 of the VFW. He was Adjutant General for the state of Alabama VFW for 20 years.

Marlin Hamilton was tireless in helping beautify Opp. He planted numerous dogwoods and other plants throughout the city. He also helped preserve Opp’s original street lamps. Marlin Hamilton was inducted into the Opp Hall of Fame in 2015.

Hamilton donated his wartime memorabilia to the Maxwell AFB Center for Aerospace, Doctrine, Research and Education [CADRE] in May 1985. Included in the donation was a key to Stalag Luft I, which was reportedly the only one in existence.

Samuel Marlin Hamilton died on March 3, 1987. His funeral was held on March 5 and he was buried in the Hickory Grove Church Cemetery near Opp, Alabama.

John Vick

The author thanks Lt. Col. Jim Lawrence, USAF [Ret] for his help in obtaining information about Hamilton. Lawrence nominated Hamilton for the Opp HOF. Thanks also to Joni Lolley with the Opp Chamber of Commerce for her help.

[Sources: Missing Air Crew Report [MACR] 9940, the 5th Air Force Archives; Opp, Alabama, Hall of Fame; the Opp Chamber of Commerce; Blog Post “The Story of The White L For Love”, by Michael D. Weber, son of Richard “Dick” Weber, waist gunner on Sam Hamilton’s B-24; Wikipedia; The Opp News, articles dated, March 25,1943, July 14, 1943, December 9, 1943; The Alabama Journal article dated March 5, 1987]