Herbert Carlisle, Captain, U.S. Army, Korean War Part 1

Published 2:00 pm Friday, April 7, 2023

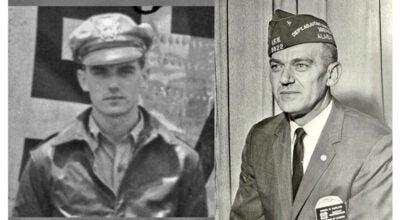

- 2nd Lt. Herb Carlisle beside his 1948 Chevrolet that he purchased in Mobile, Alabama, and drove it to his assignment at Brook Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas, in San Antonio. [Photo: Gary Carlisle]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Quoting from Herb Carlisle’s Korea diary, “Friday, October 26, 1951: It was very cold today, even though the sun was shining. Just before lunch, there were two casualties that came in. One died shortly. He had wounds to his arms, leg, chest and head. This made the noon meal a quiet one. We evacuated the other soldier by helicopter. There were four killed and seven wounded in training exercises today. It was very sad to lose so many at one time. There were land mines that the Regiment did not know about. The doctor looked like he had a really bad day.”

“November 22, 1951: We got up this morning and soon began receiving casualties. It has been raining all day and it is snowing on the mountains. The roads are in a mess. All of us were very busy tonight. We are having to go to the aid stations and get casualties in a two-and-a-half-ton truck since the jeep can’t make it through the roads. We tried to get helicopters in for some patients but couldn’t get them. One of the casualties said he was shot in the back of his head and fell and pretended to be dead. The eight North Koreans took his boots and wallet and moved on. When they left, he got up and ran back to his squad…We continued receiving casualties until very late and made our last run at 4 a.m. Each one took about three hours. Our Lt. Guy, MD, has really put in a day.”

How does a young man from Gilbertown, Alabama, find himself half-way around the world, in charge of ambulances bringing in wounded soldiers, trying to save lives during the Korean War?

Herbert Carlisle was born September 28, 1928, in the small community of Sugar Ridge, about three miles from Gilbertown, Choctaw County, Alabama. His parents were John C. and Maud Hendrix Carlisle. Herb was one of nine siblings [one died at childbirth] that grew up in a small, uninsulated, four-room log house, without the essentials of electricity, telephones and indoor plumbing. Herb recalled, “We were dirt poor but didn’t know it because most everyone around us was in the same shape. We didn’t realize we were poor until we were reading books at school that showed a better life out there.”

2nd Lt. Herb Carlisle, left, and Capt. Casey right, Medical Company, 17th Infantry Regiment in Korea. [Photo: Gary Carlisle]

In December 1947, Herb began work at Brookley Army Air Base in Mobile, Alabama. He was a clerk-typist for the Mobile Air Material Area. Starting out as a GS-2, making $1,954 per year, Herb Carlisle embarked on a career that would see him through the Korean War, continued work in the civil service, serving as Mayor of a small town in Ohio and a lifetime of helping others. Throughout his life, Herb Carlisle’s guide was the Holy Bible and his conviction of faith that began one Sunday in 1949, when he was baptized at the Dauphin Way Baptist Church in Mobile, Alabama.

Herb’s military service began when he joined the Alabama National Guard in July 1947. He was assigned to the Medical Company, 200th Infantry Regiment at Fort Whiting Armory in Mobile. Herb became the company clerk, keeping records of the men and their training. The unit’s summer training took place at Fort McClelland at Anniston, Alabama, and Fort Jackson, South Carolina.

While at Fort Jackson in the summer of 1950, Herb’s unit learned that North Korea had invaded South Korea. They also heard rumors that the 31st Infantry Division [which included their regiment] would be called to active duty. That rumor became reality on January 16, 1951. Herb had risen to Sergeant in his unit and was surprised to get a call from the State Adjutant’s Office, asking him to come to Montgomery and be sworn in as a 2nd Lieutenant.

Herb was asked to go to go to Wetumpka, Alabama, pick up a platoon that he was to command, and return to Fort Jackson where they would join the Medical Company. After training for a couple of months, Herb was assigned to the 198th Tank Battalion where he worked with a 1st Lt. who was a doctor. He trained for several months, assisting the doctor with medical sick call. Herb recalled that time, “We usually saw 30 to 40 patients a day. One day the doctor was sick and I had to see the patients by myself. I looked at their charts and asked if they were better or worse. If they were still sick, I gave them the same medication the doctor had given. My rationale was that one more day of the same medicine wouldn’t hurt them.”

In June 1951, Herb was sent to a six-week Assistant Battalion Surgeon Course at Brook Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas. He was taught the basics of first aid, including broken bones and wound care. He recalled one event that happened while he was there, “We attended a big parade for General Douglas MacArthur and his beautiful wife. Despite the fact that President Truman had just fired him for not obeying his orders, the general was being honored for his outstanding service to the country. There was a large turnout but we were able to get close enough to get a good look at them.”

After returning to Fort Jackson, Herb recalled, “I thought about my two brothers who had fought in WW II and I went to the Division Surgeon and asked to be included in the next call for officers in my category. Three weeks later, I had orders to Korea.”

Upon arriving in Korea, Herb was assigned as an ambulance platoon leader with the Medical Company, 17th Infantry Regiment. His job was to see that battle casualties were transported from the Medical Company to the Military Army Surgical Hospital [MASH]. From being around the MASH Unit, Herb said that the TV series got a lot of things right.

Herb Carlisle’s diary provides insight into the progress the Army had made in treating battle casualties since the end of WW II. The helicopter became widely used to evacuate the more seriously injured to MASH units. The treatment of severe injuries came nearer to “The Golden Hour,” that time when a critically injured patient must have life-saving intervention from the point of injury to treatment by a surgical team.

The Korean winter complicated the regular operations of Herb’s medical company. On one occasion, he wrote, “The wind and snow blew so hard that we had to hold the tent ropes to keep it from blowing away…We had six officers to the tent. We had a pot-bellied stove at each end of the tent that used fuel oil. They ran night and day. Still, when we got up in the morning, our boots would be frozen to the dirt floor…The temperature remained near 31 degrees below zero from Christmas 1951 until late January 1952.

“We had warm clothing but the men on the line still had not received cold weather clothing. They were wearing thin leather boots and lighter winter clothing…We began receiving more frostbite cases. Some feet were black from their toes to half their feet…We made sure they got winter clothing and thermal boots.”

In the spring, Herb’s company moved to a new location about eight hours away. Herb recalled, “The roads were dirt and some were treacherous. They looked like they had been cut out of the mountainside by civil engineers…When we arrived at our new camp, we were covered with dust and had no water for a bath…Our Medical Company was located about 50 yards from a 105mm howitzer…When they fired over our quarters, it would nearly roll you out of bed.”

Shortly after arriving at the new location, Herb was given the job of Supply Officer for the Medical Company. End Part 1

John Vick