James Donald Mock, Tech Sergeant, U.S. Army Air Corps, WWII

Published 1:00 pm Friday, January 6, 2023

- TSGT James Donald Mock, U.S. Army Air Corps. 159th Liaison Squadron Commando, WW II. Photo taken before he received his wings. [Photo: Bob Mock]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

SGT Donald Mock was home for a brief visit with his parents in Andalusia, Alabama, prior to deploying overseas in the war against Japan. He had just completed advanced flight training as an enlisted pilot and was assigned to the 159th Liaison Squadron. On October, 3, 1944, he received a telegram from his commanding officer, Captain Rush Limbaugh [father of the television and radio personality, Rush Limbaugh, Jr.]. The telegram ordered Mock to report to Drew Field, Tampa, Florida no later than midnight, October 6.

SGT Donald Mock’s Stinson L-5 air ambulance, “The Pride of Andalusia.” [Mock is behind the camera]. [Photo: Bob Mock]

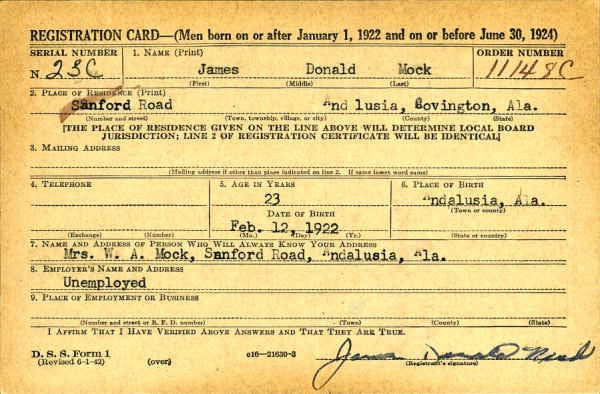

James Donald Mock was born February 12, 1922, in Andalusia, Covington County, Alabama. His parents were W. A. and Belle Moore Mock. Donald attended Andalusia schools and graduated from Andalusia High School in 1941. He enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1943 and completed basic training at Maxwell Air Base in Montgomery, Alabama. After that, he completed primary flight training at Woodward Field in Camden, South Carolina, and trained at Shaw Air Base in Sumter, South Carolina. After additional training in Texas, Mock and the 159th trained at Statesboro Army Air Field in Statesboro, Georgia. They were then sent to Cross City Army Air Base, Florida, for processing before departing from Tampa, enroute to California by train.

The squadron operated two types of aircraft: the UC-64, a single engine, utility transport that could carry 10 passengers and the single engine Stinson L-5. The L-5 was a two-passenger aircraft that could carry small amounts of freight or could be configured as an ambulance which could carry the pilot and a one wounded soldier. Donald Mock trained in the L-5 ambulance.

Training was intense, not just in flying the aircraft but in many other areas such as code, blinker communications, reading signal panels from the air and first aid. All pilots had to become proficient in these areas and learn how to escape from the plane in case of a water landing. Their most important training was learning how to take off and land on short, primitive airstrips.Shortly before leaving Tampa for California and their port of departure, the commanding officer of the 159th, Captain Limbaugh, became sick and was replaced by Lt. William G. Price III, a former P-51 fighter pilot. The squadron departed California on November 7, 1944, for the three-week voyage to Hollandia, New Guinea. After a short stop, the 159th was shipped to Leyte Gulf in the Philippines, arriving on December 1. Leyte was being attacked by Japanese aircraft as the squadron landed.

The 159th still had no planes but found a way to celebrate New Year’s Day on January 1. Somehow, they “requisitioned” enough plywood to make a dance floor before dropping leaflet invitations into the adjoining WAC compound. They were able to acquire copper tubing from the SeaBees to make a still and fashioned a bar out of bamboo. It was reported that the WACs outnumbered the men at the party.

The squadron departed for the Lingayen Gulf area on January 31, and arrived at Apache Strip near Mingaldan on February 6. The 159th was finally ready for action. They flew missions in support of the Luzon operation. Donald Mock and his squadron-mates flew as many as 20 missions a day. They directed air strikes, flew supply drops, flew courier missions, dropped propaganda leaflets and evacuated wounded troops. The 159th operated in Luzon, Cebu City, Panay and the Negros Islands. Many of their operations were with Filipino guerrillas.Mock’s primary missions were evacuating severely wounded soldiers from battle areas to safer areas in the rear for treatment. Because of pride in his hometown, Donald named his plane “The Pride of Andalusia.” After the war, he related a few of his experiences to his son, Bob.

On one mission, he landed at a make-shift airstrip near the battle zone and picked up a soldier who had suffered a severe head injury. When Mock arrived at the airfield where a hospital was located, his radio was not working. Unable to contact the ground crew and tell them about his patient, he decided to land anyway. After landing, he taxied up to the operations building but was not met by an ambulance. Mock rushed inside and explained to the officer in charge that his patient needed an ambulance and immediate treatment. The officer told Mock that the ambulance was for airport emergencies only. Mock replied, “There’s a man out there in that airplane and the only thing holding his brains in his head is a piece of gauze. If that’s not an emergency, I don’t know what is!” The officer finally relented and the soldier was taken for treatment. The situation bothered SGT Mock because he had to argue with an officer to save a man’s life.

TSGT Donald Mock’s WWII medals and ribbons [Pilot’s wings at the top and Air Medal at the bottom]. [Photo: Bob Mock]

After one mission, Mock was told to report to his commanding officer’s tent. The CO told him that his dad had died and that he intended to take Mock off flight duty for a few days. Donald Mock told his son, Bob, after the war, “I went to the woods and had a good cry, then I went back and asked to be restored to flight duty.”

Engine failures were commonplace during battlefield operations. Fuel was usually pumped from 55-gallon drums and occasionally the fuel became contaminated with water. Donald Mock had two emergency landings caused by engine failure, one of which nearly cost him his life. He recalled later, “When the engine quit, I looked around for a place to land. The best option was a nearby rice paddy. I slowed down as much as I could before touching down. As soon as the landing gear hit the water, the plane flipped upside down and I found myself hanging upside down, being held by just my harness. The harness kept me from being seriously hurt.”

As the war wound down in the Philippines, it was decided to move the 159th to Okinawa. That move of some 700 miles over water presented a real problem. The Stinson L-5 had two 18-gallon wing tanks, giving it a normal range of about 300 miles. The solution was ingeniously worked out by the squadron engineering officer, Lt. Harlan Englander and MSGT. Charles Army, the line chief.

A 75-gallon drop-tank from a P-51 Mustang was placed in the rear of the fuselage, giving the L-5 a range of more than 750 miles. On August 30, 1945, the squadron took off for Okinawa, following the lead of a Navy Catalina PBY flying boat. Despite running into rain and thunderstorms, every one of the squadron’s planes made it. Many of the planes were nearly out of fuel and one pilot requested a straight-in approach because his fuel gage read empty. His approach cut off a C-46 that was on final approach. The C-46 pilot later asked who had “cut him off.” SSGT. Lou Payerl identified himself, and the C-46 pilot, Tyrone Power, the Hollywood actor, asked him over for coffee.

The squadron’s missions on Okinawa were the same as the Philippines and many Marines owed their lives to the ambulance service provided by the Stinson L-5.

After the war was over, Donald Mock and the squadron were sent to Kanoya, Japan. They were tasked with flying into Japanese airfields to monitor the disabling of all Japanese aircraft. On November 20, 1945, Donald Mock arrived back in the States. He was honorably discharged at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, on December 5.

SSGT Mock had earned the American Theater of Operations Medal, the Philippines Liberation Service Ribbon, the Asia-Pacific Theater of Operations Medal with one bronze star, the Good Conduct Medal and the Air Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster. The original recommendation for the Air Medal reads as follows: “I certify that this enlisted man participated in 100 hours of sustained operational missions from February 6, 1945-March 22, 1945, during which time enemy fire was probable and expected. During this period, SSGT Mock ferried 450 pounds of badly needed supplies to troops in the forward area, evacuated 35 American soldiers from the battle fronts and completed 14 courier missions. Operating from Apache Strip, Luzon Island, SSGT Mock has achieved an excellent record of service. Almost daily he had been dispatched to face hazardous flying conditions. Flying over rugged and uncharted terrain and directly over enemy lines, SSGT Mock has achieved an excellent record. In one particular instance, while directing an air strike, SSGT Mock repeatedly led our bombers over the target until it was a mass of huge fires and columns of smoke. Such is one of the many instances where SSGT Mock has displayed unusual skill and resourcefulness, attributes which reflect his loyalty to duty and country.” The recommendation was signed by 1st Lt. William G. Price III, U.S. Army Air Corps, Commanding. When the citation was approved, it was signed by General George C. Kenney, U.S. Army Commanding.

After returning home, Donald Mock worked with the Coca Cola Bottling Company of Andalusia. On June 15, 1949, He married Kathleen Tubbs, a teacher at East Three Notch Elementary School in Andalusia. They would have one son, James R. “Bob” Mock. Donald Mock later worked as a wall covering contractor and Kathleen Mock founded Playpen Kindergarten which she operated for 30 years.

Donald Mock did very little flying after returning home, but he shared his wartime experiences with his son, Bob. His dad’s stories about flying in WW II greatly influenced Bob to pursue a career in aviation. He became a pilot at an early age, then a flight instructor and air traffic controller. Bob retired in 2013 after 30 years with the Federal Aviation Administration. Bob is married to the former Joanne Rawls of Gantt, Alabama. They currently reside in Madison, Mississippi. They have three children and three grandchildren.

Donald Mock died June 22, 1979 in the V.A. Medical Center, Montgomery, Alabama. His funeral was held on June 24 at Foreman’s Funeral Home chapel. Burial with full military honors was held at Stone Lake Gardens, Andalusia, Alabama. He was survived by his wife, Kathleen Tubbs Mock; and a son, James R. “Bob” Mock. Kathleen Mock died February 8, 1998.

John Vick

The author would like to thank Bob Mock for his help in telling his dad’s story. The author still remembers his first-grade teacher at East Three Notch Elementary School, Miss Kathleen Tubbs. All three of the author’s daughters attended Playpen Kindergarten.

[Sources; Wikipedia; “Overseas and Combat History of the 159th Liaison Squadron Commando,” 3rd Air Commando Group, Fifth Air Force, Nov. 7, 1944-Seo. 10, 1945; “Dick Barr and the Air Commandos,” excerpted from “WW II Air commandos, Vol. II,” 1994 by Dick Barr].