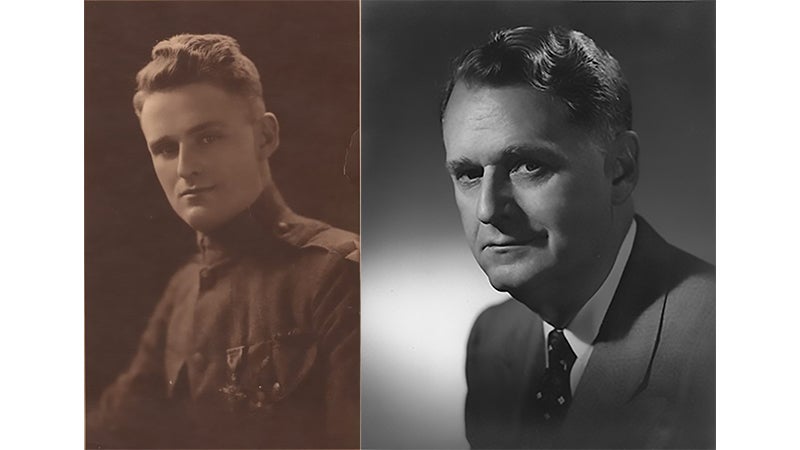

William Earl Campbell [William March], Sergeant, U.S Marine Corps, WWI Distinguished Service Cross, French Croix de Guerre

Published 2:30 pm Friday, August 12, 2022

- LEFT: Sergeant William E. Campbell in WWI Marine Corps uniform. [Photo: encyclopediaofalabama.org] RIGHT: William March [William Campbell] postwar author. [Photo: encyclopediaofalabama.org]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

William March was the adopted pen name of William Earl Campbell, a much-decorated Marine veteran from World War I. After the war, he became a successful businessman but is better known for his fictionalized stories of WW I and his early life, growing up in south Alabama.

William Earl Campbell was born September 18, 1893 in Mobile, Alabama. His parents were Susan March and John Leonard Campbell. The family was poor and moved often as the father sought work in the sawmill towns of northwest Florida and south Alabama. He worked as a timber appraiser, evaluating tracts of timber for sawmills. As the second of eleven children, William found life difficult and left school at the age of 14 to take a job working in the office of a lumber mill in Lockhart, Alabama.

After two years, William moved back to Mobile and went to work in a law office to earn enough money for school. He eventually earned his high school diploma from Valparaiso University in Indiana. He moved back to Alabama and studied law for a year at the University of Alabama, before moving to New York City in 1916. He worked in a law firm there until June 1917 when he decided to join the Marine Corps. Like a fellow native of Mobile, Eugene Sledge, some 25 years later, March’s decision to join the Marine Corps was a defining point in his life [more on that later].

After Marine Corps boot camp at Parris Island, South Carolina, Campbell shipped out from Philadelphia and arrived in France in February 1918. He was assigned to the 43rd Company, 5th Regiment of the 2nd Marine Division. The 43rd Company was involved in every major engagement involving American troops and would suffer heavy casualties.

Campbell first saw action at Verdun near Les Eparges and then at Belleau Wood where he was wounded. After spending time recovering in the hospital, he took part in the Aisne-Marne offensive in July and the Battle of Saint-Mihiel in September. Campbell was promoted to Corporal and then to Sergeant because of his actions.

In October, Campbell was assigned to French troops in the Blanc Mont area. The Blanc Mont ridge [east of Reims] was a key area held by the Germans. During the assault on Blanc Mont ridge on October 3, Campbell was wounded and sent to a frontline medical station for treatment. The Germans counterattacked the next day and had advanced to within 300 yards of the medical station where Campbell was being treated. Campbell left the station and made his way to the battlefield to help wounded soldiers. Although wounded himself, he helped repel the German attack and refused to be evacuated until the Germans were beaten back.

For his heroic actions during the Blanc Mont battle, Campbell was awarded the French Croix de Guerre as well as the Distinguished Service Cross, our nation’s second highest award next to the Medal of Honor. The U.S. Navy established the Navy Cross in 1919 and Campbell also received that award. Although Campbell would physically recover from his wounds, the bloody trauma of hand-to-hand combat left a psychological scar that stayed with him the rest of his life.

After the war ended, Campbell was assigned to the occupation force. He studied briefly at the University of Toulouse, before returning home where he was discharged in August 1919. He found work at the Waterman Steamship Corporation as the personal secretary for John B. Waterman, the founder and company president. Campbell advanced quickly in the company, becoming vice-president then traffic manager. When the company opened an office in Memphis, he moved there and managed the new office for two years.

Campbell traveled the country and abroad, working for Waterman in New York City, London, England, and Hamburg, Germany. Friends of Campbell recalled that he was widely read, particularly books on psychology. The effects of the war caused him to suffer from what we now call PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder]. He moved to New York City in 1928 and took creative writing classes at Columbia University.

During the 1920s, Campbell began writing stories that revolved around his wartime experiences as well as his childhood memories of south Alabama. He sent his stories to different publishers using different pseudonyms. His first published story was “The Holly Wreath,” published in 1929 by the New York literary magazine, The Forum. He had used the pen name William March [after his mother’s maiden name]. From that time on he published under William March, which is the name we know him by today.

After his first success, March’s stories were published in several literary magazines including Contempo, Prairie Schooner as well as The Forum. Several of his stories were printed in O. Henry Prize Stories. Between 1930 and 1932, he had more than 20 stories published. His first novel, “Company K,” was published while he was still in New York, working for Waterman.

“Company K” is recognized today as a WW I classic, alongside “All Quiet on the Western Front,” by the German author, Erich Maria Remarque.

March’s book is a collection of 113 short stories, some as short as a few paragraphs, told by different soldiers. The first story in the book is a sort of introduction as told by Private Joseph Delaney, the author of all the other stories. Most readers assume that Delaney is, in fact, William March. If there is a purpose to March’s individual soldier’s stories, it is to tear down the veneer of a “good war.” Those soldier’s stories tell about being cold and fatigued, hungry, scared and confronted by death – sudden, brutish, constant death that dulls the senses.

March finished his second novel, “Come in at the Door,” while he was assigned to Hamburg, Germany, for Waterman. The novel was the first of his “Pearl County” series of books and short stories set in south Alabama, using fictional town names. They recalled his impoverished childhood and the fight to survive.

While in Hamburg, he also wrote a short story, “Personal Letter.” The short story expressed March’s concern over Adolf Hitler and the rise of Nazism in Germany. Because of concern for his German friends, the story was not published until later when it was included in “Trial Balance: The Collected Short Stories of William March.”

March published a short story collection, “The Little Wife and Other Stories,” while in London in 1935. The next year he published the novel, “The Talons.” Both the novel and the short story collection relied on his early memories of south Alabama. It was reported that March underwent psychoanalysis while in London, in an effort to overcome his depression from the war.

In 1937, March retired from Waterman and moved to New York City. While there, he published “Trial Balance: The Collected short Stories of William March,” and one other collection, “Some Like Them Short.” March published the novel, “The Looking Glass,” in 1943. It was set in a fictional town in Alabama. Many consider it his best novel.

Psychological problems along with depression resulted in serious health concerns for March and friends encouraged him to move back to Mobile. He moved there in 1949 and then to New Orleans in 1950. While there, he published his fifth novel, “October Island,” in 1952 and his last novel, “The Bad Seed,” in 1954. William March died in New Orleans on May 15, 1954. He did not live to see the success of his last novel, “The Bad Seed,” which was adapted for a Broadway play that ran in New York City and London. Warner Brothers made it into a film which was released in 1956. A last work by March, “99 Fables,” was published by the University of Alabama Press in 1960.

As mentioned earlier, William March and Eugene B. Sledge were both born in Mobile, Alabama, and there were parallels in their lives. They both fought in wars and authored books that became classics. They both served in the 5th Marine Regiment in two different wars. However, these two men from the same city led totally different lives.

Sledge’s “With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa,” is a memoir of his WW II service in the U.S. Marine Corps. It is his first-person witness to all the horrors and atrocities of war. Like March, Sledge was haunted for the rest of his life by those memories but he had the support of family and friends. Sledge was a family man and a scientist who received his doctorate and became a college professor. He and his family embraced the popularity that came with the acclaimed success of his book. He worked closely with Ken Burns in filming the World War II documentary, “The War.”

On the final page of “With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa.” Sledge wrote, “War is brutish, inglorious and a terrible waste. Combat leaves an indelible mark on those who are forced to endure it. The only redeeming factors were my comrades’ incredible bravery and their devotion to each other. Marine Corps training taught us to kill efficiently and to try to survive. But it also taught us loyalty to each other – and love. That esprit de corps sustained us.”

March wrote “Company K” from a third-party viewpoint. Through the 113 soldier’s stories, he describes the horrors that March himself remembered. The book is a written record of the shock and callous attitudes that take over soldiers’ lives when they are repeatedly exposed to scenes of maimed, dead and dying friends and enemy alike. March wrote a cynical narrative that lays bare the soldier’s feeling of utter futility of fighting a barbaric war, far removed from the crowds and marching bands that celebrated their departure from home.

William March never married and jealously guarded his private life. When he died, his family and literary executors honored his request for privacy. He left few if any personal notes, leaving his written works as his legacy.

John Vick

Sources: Wikipedia; Alabama Review, Vol. 66, Issue 1, “William March and Eugene B. Sledge, Mobilians, Marines and Writers”; Encyclopedia of Alabama, “William March,” By Jessica Lacher- Feldman [University of Alabama] and Aaron Trehub [Auburn University]; “Company K,” by William March, 1933; “With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa,” by Eugene B. Sledge, 1981].