William L. Ward, PFC, U.S. Army Air Force, WWII Japan POW

Published 4:30 pm Friday, January 28, 2022

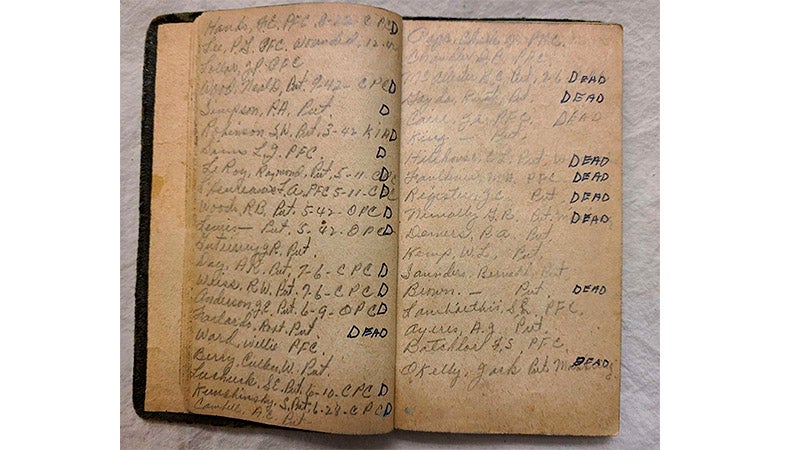

- PFC. Willie Ward's name is listed in this diary kept by Charles D. Page, a POW at the Cabanatuan prison camp in the Philippines. Page recorded the names of the 27th Bombardment Group that were held at the camp. His diary records in pencil, the names and fate of the the 212 men from the 27th. "D or Dead" was written by the names of the men who died. Of the 39 men listed here, only 16 survived, including PFC Willie Ward. [Photo: The National WW II Museum]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The William Moses Ward family had three sons that served in the U.S. Army Air Force during WW II: Marvin I. Ward, Preston J. “P J” Ward and William L. “Willie” Ward. P J Ward became a B-17 pilot and was shot down over Germany and taken prisoner. We will write about him in next week’s column. We hope to write about Marvin I. Ward at a later date. Willie Ward became a prisoner of war when he was captured on Corregidor. He is the subject of this week’s column.

During WW II, the Ward family had the unwelcome distinction of having two sons who became prisoners of war, half-a-world apart.

Author’s special note: This remarkable story of survival against incredible odds is a testament to the courage, sheer fortitude and triumph of the human spirit of one man – PFC. William Lewis “Willie” Ward of Covington County, Alabama. It is an honor and privilege to tell his story.

William Lewis “Willie” Ward was born in the Mobley Creek community in Covington County, Alabama, on October 25, 1918. His parents were William Moses and Mary Frances Hassel Ward. They lived near the William E. Ward, Sr. family. Both Ward families had several sons who served their country during WW II. Willie attended area schools and graduated from Andalusia High School before joining the Army Air Force in early 1941. He married Gladys L. Kay on September 10, 1941. At the time, Willie was a member of the 27th Bombardment Group Light stationed at Barksdale Air Force Base near Bossier City, Louisiana. The 27th began shipping out to the Philippines by way of Savannah, Georgia, in November 1941. Willie Ward was assigned to the Headquarters Group, 27th Bombardment Group and left Savannah for the Philippines. He arrived just before the Japanese attack that happened on December 8 [because of the international dateline, that was the same day that Pearl Harbor was attacked].

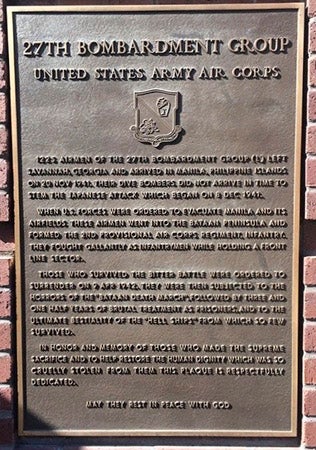

Memorial marker to the 27th Bombardment Group that departed from Savannah, Georgia, from November-December 1941. The marker is located at the Andersonville National Historic Site near Andersonville, Macon County, Georgia. [Photo: Makali Bruton, Dec. 2017]

In August 1942, Willie’s sister, Mrs. Lucille Ward Stephens received a telegram stating that he was “missing in action.” As it turned out, Willie had been taken prisoner when the American forces surrendered Corregidor to the Japanese. Corregidor was an island located at southern tip of the Bataan peninsula. The captured Americans and Filipinos were marched some 65 miles north to two prison camps, O’Donnell and Cabanatuan. That forced march became known as The Bataan Death March. More than 500 American prisoners died on the march. Records show that Willie was taken to the Cabanatuan prison camp. Of the estimated 5,000 POWs held at the camp, there were more than 2,764 burials recorded. Willie was one of the survivors who were eventually moved to mainland Japan to be used as forced laborers.

In December 2020, an article was published by the National WW II Museum in New Orleans that described a diary written in pencil by a Cabanatuan POW, Charles D. Page. The diary describes the lives of 212 POWs who were members of the 27th Bombardment Group. The diary lists the men by name, rate or rank, and shows whether or not they survived by noting “D or Dead.” On the two pages reproduced for this article, there are 39 names listed with only 16 survivors. One of the survivor’s listed on the first page is the name of PFC Willie Ward.

After the war, Willie related two stories to his cousins, Wyley and Richard Ward. During the Bataan march, the Japanese guards would shoot anyone who fell out from exhaustion. Willie said that he marched with his hands on the shoulders of the man in front of him and cat-napped while marching. He would swap positions with the man in front so that he could do the same. That was how he survived the march.

The second story came from his time at the Cabanatuan POW camp. Willie had done something that angered one of the guards The guard tied Willie’s hands and feet, placed him in an old bathtub and filled it with ice. Willie said that his life was saved when a Japanese officer came by, picked him up from the tub and threw him through a window into the prison courtyard. Willie’s fellow prisoners untied him and carried him to their quarters.

Willie’s survival was the beginning of an ordeal that lasted until the end of the war, when he was finally released from a Japanese prison camp on mainland Japan.

On June 24, 1943, Willie’s sister Lucille received confirmation that Willie was a POW. In a telegram from the provost Marshall General, she was informed that the International Red Cross had reported that “your brother, Pvt. Willie L. Ward is a prisoner of the Japanese Government in the Philippine Islands.” That was the first information she had received since he was reported missing in action.

Willie was moved from the Cabanatuan camp on September 20, 1943 and placed on a transport ship, the Taga Maru. He was taken to a prison camp in central Japan. He survived the voyage and that in itself was miraculous. The Taga Maru was sunk on a later voyage.

In May 1942, Japan had begun transferring POWs to mainland Japan by sea. The transports were called hell ships because of the horrendous living conditions for the prisoners. They were crammed into cargo holds with little air ventilation, little food and water on voyages that could last weeks. Because those ships carried a mix of prisoners, Japanese troops and cargo, they could not be marked as non-combatants and were therefore prime targets for allied planes and submarines. More than 20,000 allied POWs died at sea when 15 of those transport ships were sunk. PFC Willie Ward had survived the Bataan march, the Cabanatuan prison camp and a treacherous sea voyage but still remained a prisoner of the Japanese.

We have no records of where Willie was transferred other than “to a prison camp in central Japan.” The Osaka prison group is a possibility but we have no records showing that Willie was there.

Records indicate that Willie was transferred again on May 21, 1945, to a prison within the Nagoya prison group. There were 14 individual POW camps in the Nagoya district and Willie was transferred to prison #9-B Sinzu, located in the city of Toyama, in the Toyama Prefecture. It was called Toyama Iwase. Willie was among the 230 American and 119 British and Australian prisoners at #9-B. Conditions at that camp were better as evidenced by the fact that only one POW died at the camp before it was liberated in August.

After the camp was liberated, Willie’s family received notice that he had sailed from Manila in September and was on his way home. The Andalusia Star noted in its November 1, 1945 edition that “Willie Lewis Ward had arrived in Andalusia last Friday for a brief visit with his sister, Mrs. Harvey Stephens.” We can only imagine the reunion at the Ward home when Willie came back to be reunited with his brother, P J Ward, who had returned home in June from two years in a German POW camp.

After the war, Willie Ward worked with his father-in-law, Elijah Kay who ran a planer mill near Florala, Alabama. It’s possible that the mill was moved to Houston County because that’s where Willie died on May 17, 1990. His wife Gladys died January 20, 1995. They are both buried at the Garden of Mercy Cemetery at Kinsey, Alabama. They had no children.

John Vick

[The author thanks Richard and Wyley Donald Ward for their recollections of their cousin, Willie Ward]

{Sources: Wikipedia; the book, “The Steadfast Line” by Mary Cathrin May; The National WW II Museum article, Curator’s Choice, “The Book of the Dead and the Dying” Dec. 9, 2020; National Archives Prologue Magazine article “American POWs on Japanese Ships Take a Voyage into Hell”, 2003, Vol. 35, No. 4; Preliminary Japanese POW Camp List of all known POW camps in Japan, prepared for the War Crimes Legal Proceedings, SCAP files; Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, Historical Report, “U.S. Casualties and Burials at Cabanatuan POW Camp”; The Andalusia Star article dated July 1, 1943; The Montgomery Advertiser article dated August 30, 1942; The Andalusia Star article dated November 1, 1945]

Memorial marker to the 27th Bombardment Group that departed from Savannah, Georgia, from November-December 1941. The marker is located at the Andersonville National Historic Site near Andersonville, Macon County, Georgia. [Photo: Makali Bruton, Dec. 2017]