Marcus Randolph Kyzar, Major, U.S. Army Air Force, WW II, and U.S. Air Force Veteran

Published 12:11 pm Friday, September 17, 2021

- Captain Randolph Kyzar, U.S. Air Force post WW II portrait. [Photo: the Kyzar family]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Randolph Kyzar was one of at least two Andalusia High School graduates to fly The Hump during WW II, the other being Dempsey Albritton [see Andalusia Star-News article dated July 3, 2021]. The dangerous supply missions referred to as flying the Hump involved some of the most hazardous flying conditions experienced during WW II. Before his tour in the CBI [China-Burma-India] theater was finished, Randolph Kyzar had completed 824 flight hours.

Marcus Randolph Kyzar was born October 4, 1922 in Goshen, Alabama. His parents were Dr. James Hugh Kyzar and Clara Soloman Kyzar. Randolph had two older brothers, James Hugh Jr. and Terril Franklin. A few years after Randolph’s birth, the family moved to Andalusia, Alabama where Dr. Kyzar set up a medical practice.

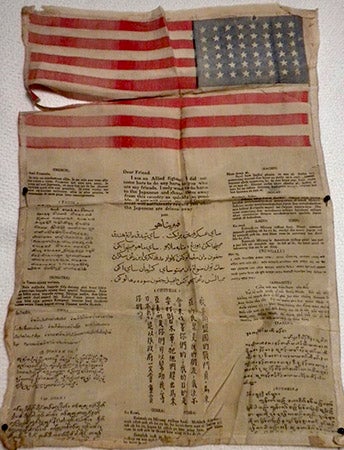

Silk-screened print from 2nd Lt. Randolph Kyzar’s flight jacket [WW II]. Note the message is in 17 languages with 48 star flag. [Photo: the Kyzar family]

Basic flight training began in 1943 at Santa Ana Army Air Force Base in California. Randolph received his pilot’s wings in multi-engine transport and was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in late summer of 1943. His first deployment began right around his 22nd birthday in October when he received orders to report to the CBI theater of operations in India.

Imagine the daunting task of navigating from the United States to India in 1944. The squadrons of C-47s flew from Presque Isle, Maine to Gander Newfoundland. After crossing the Atlantic, they landed in the Azores, just off the coast of Portugal. From there it was on to Marrakech, Morocco, then to Tunis, Tunisia. During the brief stop in Tunis, Randolph met with his brother, Terril, who was serving with the U.S. Army in North Africa. According to Randolph, their “night on the town” nearly caused him to miss the departure the next morning. From Tunis they flew to Cairo, Egypt, then on to Alerdan, Persia [modern day Iran]. They arrived in Karachi, India [Karachi became the capital of the newly created Pakistan in 1947], and flew to Agra before arriving at their base in Chabua. Randolph’s squadron was sent to Warasup which would be his main base of operations for his flights to China.

The supply flight from India to China was about 530 miles but the flight and return were some of the most hazardous flown by the Army Air Force during WW II. There were few navigational aids. Flying in bad weather over and around mountains reaching nearly 20,000 feet was inherently dangerous. Adding to that winds that sometimes exceeded 100 miles per hour aloft made the round-trip flight even deadlier. During the entire operation, the Air Transport Command lost about 600 aircraft and more than 1,000 men.

New pilots arriving for duty were given a check-out flight to China. On the flight, the Operations Officer sat in the pilot’s seat and the new pilot in the copilot’s seat. Randolph would never forget his check-out flight. When they arrived over the drop-zone, the planes assumed a holding pattern while they slowly descended, allowing the lowest plane to shove their cargo pallets out the back door [each pallet had an attached parachute]. Randolph had heard some radio chatter about buzzards near the drop-zone. As he was readying for the drop, a buzzard struck the nose of the plane, crashed through the Plexiglas windscreen on the copilot’s side and slammed into the bulkhead behind him. Luckily, Randolph was able to duck out of the way and only received minor cuts from the shards of Plexiglas.

It would be difficult to overstate the challenges faced by the pilots flying The Hump. With so few navigational aids, navigating the mountain passes was largely done using direction, time and distance. A flight that was difficult under visual flight restrictions in good weather was immensely more dangerous when fog and rain had set in. Randolph recalled one plane that failed to make a timely turn and crashed into the side of a mountain.

By the time Randolph Kyzar began flying The Hump, the threat faced from Japanese fighters had largely been neutralized. However, there was still the threat of being shot down or otherwise going down in hostile territory. Each American airman carried a silk-screened print, sewn inside his flight jacket that had an Emergency Message printed on it: “I am an Allied fighter. I did not come here to do any harm to you who are my friend. I only want to do harm to the Japanese and chase them away from this country as quickly as possible. If you will assist me, my government will sufficiently reward you when the Japanese are driven away.” The message was printed in 17 languages and the print also had a 48-star American flag. That print from inside Randolph Kyzar’s flight jacket was a cherished memento that he brought home after the war.

Randolph completed the required flying hours to be rotated back to the States in May 1945. The Air Transport Command required 800 flight hours in theater and Randolph had completed 824 hours. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross with two Oak Leaf Clusters as well as the Air Medal with four Oak Leaf Clusters.

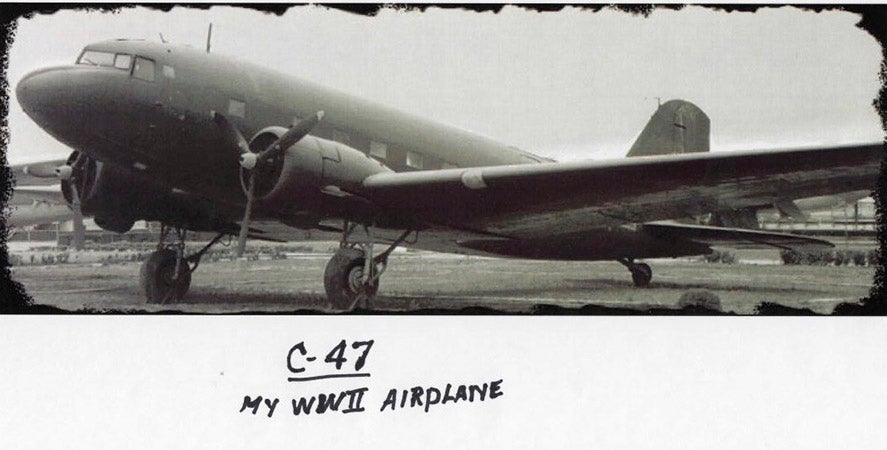

C-47 U.S. Army Air Force transport flown by 2nd. Lt. Randolph Kyzar in the China-Burma-India operation

known as “Flying the Hump.” [Kyzar’s notation – “My WW II airplane” [Photo: the Kyzar family]

Randolph and Mary lived in Ft. Walton Beach, Florida. In August 1951, he was assigned to Erding Air Force Base in Munich, Germany. While there, their daughter, Karen Patricia, was born in 1953. They returned stateside to Randolph AFB at San Antonio, Texas, in 1954. A son, Marcus Randolph Jr., was born there in 1955. Randolph had continued flying transport planes for the Military Air Transport Service [MATS], the new name for the Air Transport Command after the war.

In 1956, Randolph was assigned to Moody AFB in Valdosta, Georgia. During that time, the Air Force reduced its pilot numbers by decertifying some from flight status. Randolph was one of those pilots decertified and subsequently trained in radar operations. As a trained radar officer, Randolph was sent to the 626th Airborne Control and Warning Squadron located on Fire Island, Alaska. The small island was located about nine miles from Anchorage. The base was part of NORAD’s air defense system and was equipped with the Nike surface-to-air missile. Randolph spent 1959-60 in Alaska while Mary took the family home to Andalusia where they stayed at the Gables Apartments.

After his Alaska assignment, Randolph was sent to Tyndall AFB in Panama City, Florida where he was promoted to Captain. From 1963-65, Randolph served with the Regional Recruiting Office Command in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and was promoted to Major. From 1965-66, he served in Maintenance and Supply at Sheppard AFB in Wichita Falls, Texas. In 1966, Randolph received orders to go to Vietnam. He served the next two years in Maintenance and Supply at the U.S. base located at Tuy Hoa, South Vietnam. His family moved back to Andalusia to await his return. In 1968, Randolph returned to the States and retired with the rank of Major and 26 years of accumulated service.

The family settled in Andalusia and Randolph took a position as pharmacist at Columbia Regional Hospital. He reopened a retail pharmacy at the hospital and managed pharmaceuticals for the hospital’s patients and the adjacent nursing home. He remained at the hospital until it closed in 1984. After that, he worked at Harco Drugs and with several other drug stores as a relief pharmacist. He last worked as a relief pharmacist for Horace Bailey at City Drug store in 2012. Randolph Kyzar died in July 2013, just three months shy of his 91st year.

John Vick

The author would like to thank Mary Kyzar and her son, Marc, for their assistance in preparing this tribute to Randolph.

[Sources: Wikipedia; u-s- history.com; “Flying the Hump During WW II”, Lyon Air Museum]