Part 2: Wesley E. Courson, 2nd Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Force, WWII POW, Stalag Luft III

Published 3:29 pm Friday, July 30, 2021

- Oct. 28, 1943 photo of the awarding of the Air Medal to Mrs. Luther Courson for her son, 2nd. Lt. Wesley E. Courson who was a POW in Germany. Shown [L-R], Mary Courson [Kyzar], Wesley’s sister; Mrs. Lena Courson, his mother; Mr. Luther Courson, his father; Mayor J. G. Scherf of Andalusia and Col. James Daniel, Jr. Shown on the left in the back is Wesley’s sister Lois Courson [Hein]. (Photo: Marc Kyzar)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Stalag Luft III was one of the most infamous and well-known of the German Prisoner of War camps. It eventually housed some 10,949 POWs, including 7,500 U.S. Army Air Force prisoners. The prisoners called themselves Kriegies, a shortened slang term from Kriegsgefangene, the German word for “Prisoner of War.” The camp was located at the town of Sagan in the Nazi province of Lower Silesia [now Poland]. It became famous after the war because of two movies that depicted escape attempts by British Commonwealth POWs. The first was “The Wooden Horse,” released in 1950. The second, more famous film, released in 1963, was “The Great Escape,” after the 1950 book of the same name written by Paul Brickhill. It starred Steve McQueen, James Garner and Paul Attenborough. Wesley Courson would spend approximately 20 months at Stalag Luft III.

2nd Lt. Wesley Courson had been injured by the bomb bay doors as he parachuted from his damaged B-17. His injuries were compounded further from the hard impact with the ground. It had taken him about 17 minutes to fall from 27,000 ft.

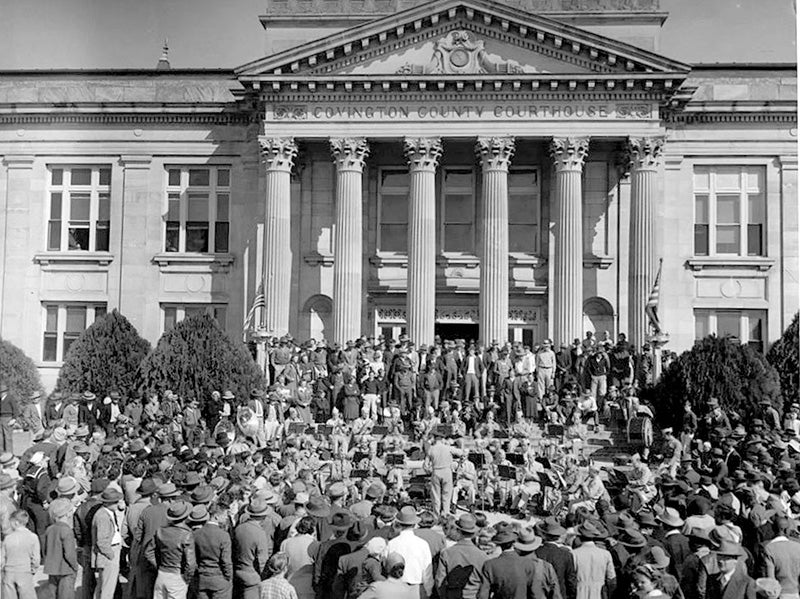

In Oct. 1943, a large crowd gathered at the Covington County Courthouse in Andalusia to see the U.S. Army Air Force Air Medal awarded to Mrs. Luther Courson for her son 2nd Lt. Wesley E. Courson, who was a POW in Germany at the time. (Photo: Marc Kyzar)

Courson lay in a pain-filled daze when he was suddenly confronted by five German Border Guards. They quickly realized that he would was not a threat and carried him in a wheel barrow to a nearby farm house, leaving him beneath a shade tree. Courson recalled the scene, “I lay under that tree for over five hours waiting for transport. My leg and side were about as big as the rest of me and the pain had changed to agony. A little girl came over to me, she was perhaps no more than six, looked at me with deep hurt showing in her pretty face….with little legs and feet flying, she ran into the house. Carefully, she returned and handed me a mug of cool water. That has to be the one drink of water most outstanding in my life. It was more than just welcome taste…it had so much more than welcome taste…it had feeling and care of one small lady to a human heart. I remembered that the Germans might take my wallet…my watch was gone, lost in the jump. When I finished the water, I slipped my wallet and a picture of my girlfriend into the mug and handed it back. The little feet did the distance to the house in half the original time. She didn’t come back but I saw her looking from the door.”

Almost 29 years later, Wesley Courson would learn that her name was Fien Mallema. In 1972, he received a letter from a Mr. Jansen who was writing a book about the WW II air war over the Netherlands. He informed him that the young girl who brought him the cup of water was now married and her name was Fien Reitsma-Mallema. Jansen wrote, “The woman still treasures your wallet with a photograph of you [yellowed, not good for reproduction]…it did not contain your address so she could not return it to you…I am sure she will be thrilled to hear that I have ‘found’ you.”

After five long, pain-filled hours, a Germans ambulance arrived to transport Courson to a hospital. His bombardier was in the ambulance and uninjured. On the way to an Amsterdam hospital, he told Courson that the rest of the crew that parachuted had been captured and were on the way to prison camps. Courson’s B-17 had fought the Germans all the way from Hannover to just across the Dutch border where it crashed. At the hospital, they were reunited with the plane’s engineer whose eyes were bandaged.

Courson’s leg was placed in a cast at the hospital and he was sent to Hallmark Hospital in Dulag, Germany [near Frankfort] and arrived on August 11, 1943. He was placed in solitary confinement upon arrival. During his eight-day stay, he was interrogated and had his cast removed. He was then moved by train to a British-operated hospital near Memmingen. Courson noted that there were lots of British POWs at the hospital, many of whom had been there for three or four years. After a few weeks, they were moved to another British-operated hospital at Kloster-Haina near Kassel. The hospital was housed in an old monastery. The doctors there were able to remove a piece of plexiglass from the engineer’s eyes and he had his vision partially restored. It was during Courson’s stay there that he and another officer tried to escape. They had secured some maps, a compass, some food and water and waited for an opportunity. On September 16, 1943, they got their chance. The Chief Doctor at the hospital held an inspection of all the guards. Only two guards were left to guard the hospital, so Courson and his buddy went through the fence in the rear when the guards were around front. He recalled, “We took up a compass course toward Switzerland and southern France. We walked at night, eating and sleeping during the day. At the end of three days…the hills were getting steep and high. We hadn’t had many narrow escapes….so we tried to walk through a town to keep from climbing another mountain. The Gestapo caught us about the middle of the town of Kirchain, Germany. We had only walked about 35 miles.” They were taken to a prison near Zeigerheim, Germany, where they were put into solitary confinement. After they were interviewed by the Commandant, things improved somewhat. Courson recalled, “He got quite a kick out of our escape story [which we stretched]. He said we were the first American prisoners and we were quite a novelty. He cancelled part of our sentence and gave us back our belongings along with some books and cards. They were sent to adjoining cells where they were guarded by two young soldiers. The guards brought them Red Cross packages with plenty of food and cigarettes. Courson said, “The German lads had nothing so we made arrangements [for a sum of food and tobacco] to let us stay together during the day and eat together. Then we gave them a can of real coffee and they were ours from then on. They brought us extra bread, cheese…and tomatoes.” They learned that the two young guards had been wounded at the Eastern Front and had been returned to guard duty. After a week, they were returned to the camp at Kloster-Haina.

In July, Courson was notified that they would be sent to the American Prisoners of War Camp at Sagan, Germany.He had been shot down on July 26, 1943 and arrived at Stalag Luft III on October 8, 1943. Courson would become Prisoner of War No. 1642 at the prison camp.

Less than three weeks later [as reported in the Andalusia Star on October 28, 1943], the city of Andalusia held a ceremony in front of the courthouse. Army Air Force Col. James Daniel, Jr., along with Andalusia Mayor. J. G. Scherf, presented the Air Medal honoring Wesley Courson to his mother Mrs. Luther Courson.

As a side note, Courson’s mother would receive a letter in April 1944 from a Canadian POW, Captain F. J. L. Woodcock, who had been sent home because he had lost his sight. He told her that he had known her son at Kloster-Haina and that Courson was doing well. He also told about Courson’s brief escape with Harry Younge from Maryland. He closed with an upbeat note, “If his letters to you contain half the pep and fun he showed in prison life, you have nothing to worry about. Keep his letters rolling along as they are such a help to break the monotony of that life.”

Upon his arrival at Stalag Luft III, Courson was happy to see many of the men he had trained with back in the States. He also found several of his crew who had parachuted from the plane. Courson was assigned to the South Compound, Block 131, room 2. He recalled, “The compound consisted 14 blocks plus the theater building. Each block had about 15 rooms. I lived in a 10-man room with double bunks. The blocks were over-crowded with little floor space and you had to get used to the straw-filled mattresses…Guard posts were located at intervals around camp. Guards were armed with rifles and machine guns and there were searchlights in the towers. The camp was fenced with double rows of heavy, braided wire, rolled barbed wire between the fences and an inner guard-rail about 30 feet inside the fence.”

The men received one Red Cross food parcel per week. They could receive parcels from home that came via Switzerland and were then inspected by the Germans upon arrival. The prisoners were called to “appell” [German for roll-call] twice a day and often at odd hours so that the barracks could be searched. The prisoners called the guards “goons.” They convinced the guards that it stood for “German Officer Non-Com”, so the guards went along with the nickname.

There were several escape attempts by prisoners during Courson’s time there. The most famous one was depicted in the film, The Great Escape. A group of British Commonwealth prisoners developed an elaborate escape attempt in 1944. Their plan to tunnel out of the camp was so secretive that they referred to the tunnels as Tom, Dick and Harry. More than 600 prisoners were involved in digging the tunnels. RAF Squadron Leader Roger Bushnell [codename “Big X”] developed and led the attempt. He planned on getting at least 220 prisoners out, all wearing civilian clothes and some with forged papers. For various reasons, Tom and Dick were abandoned and Harry finished. During the escape using Harry, they were discovered and only 76 of the planned 220 made it out safely. The Germans captured 73 of the 76. Hitler wanted all of them executed but decided on “more than half” out of fear of reprisals against German POWs. At least 50 were executed including Roger Bushnell.

Courson complained about the atrocities committed by guards, “We had one of our Colonels shot through both legs at night…the Goon guard claimed he saw movement outside the barracks….During one daylight air raid, one of our Sergeants working in the kitchen was shot through the head and killed. More than thrice the guards have shot into the barracks at night.

Courson recalled one of the worst atrocities, “About 80 Swedish officers escaped through a tunnel and were free for a few days. They were captured by the Gestapo and shot ‘en masse’ without trial.” It’s possible Courson was referring to the escape attempt described in the movie “The Great Escape.”

Courson recorded other complaints, “They leave the water off, leave the lights off, hold back parcels and mail, cut down on bread, potatoes, refuse to let us have fires in our stoves, promise showers and never install them and countless other things to irritate us. It is constantly implied to us that the people back home think we are at summer camp. I wish to Hell they were permitted to know just the half of it.”

End Part 2

John Vick

[Sources: Wikipedia; history.net; The American Air Museum in Britain; Andalusia Star article dated Oct. 28, 1943; special thanks to 2nd Lt. Wesley E. Courson’s sister, Mary Kyzar and her son Marc for furnishing a copy of his wartime diary]

More COLUMN -- FEATURE SPOT