The Cuban Missile Crisis – “October 27, 1962 – Black Saturday”

Published 10:33 am Monday, November 2, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

For 13 days in October 1962, the United States and the Soviet Union stood face to face in a diplomatic standoff that nearly ended in nuclear war.

The Cuban Missile Crisis was precipitated by the Soviet Union’s placement of nuclear missiles in Cuba. President John F. Kennedy reacted with a quarantine of all offensive military equipment being shipped to Cuba. When the crisis ended, the Soviet Union had agreed to remove its missiles from Cuba and in a separate, secret agreement, the United States had agreed to remove its nuclear missiles from Turkey. With no “hot line” between Washington and the Soviet Union in 1962, the negotiations were difficult and complex, with much distrust on both sides. Not until an agreement on the night of October 27, did the two countries step back from the brink of nuclear war. That last day of negotiations was fraught with several unexpected events that nearly ended in tragedy. That day thereafter would be referred to as Black Saturday.

What transpired during that last week of intense negotiations is still little known by the American public. The U.S.response and subsequent negotiations were led by President Kennedy after meetings with his Executive Committee of the National Security Council, ExComm. From the Soviet side, decisions were made by Premier Khrushchev and members of the Kremlin’s inner circle. Two key Soviet officials in the U.S. were contacts between the President and the Kremlin: Andrei Gromyko, the Soviet Foreign Minister and Anatoly Dobrynin, the Soviet Ambassador to the United States.

Adlai Stevenson, who was then U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, went before the U.N. Security Council on October 23rd to explain the crisis. The U.N. gave little satisfactory response to the charges brought by Stevenson. Because of their inaction, President Kennedy would not rely on the U.N.

Throughout the discussions between Kennedy and his ExComm staff, there was an ongoing battle between the so called “hawks and doves.” One group had always wanted an excuse to go into Cuba and “wipe Castro off the map.” Others counseled the President to use diplomacy to get Khrushchev to remove the missiles.

During the negotiations, the most confidential information was passed back and forth between Ambassador Dobrynin and the President’s brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. Their last meeting on the evening of October 27 may have averted nuclear war.

In the midst of the negotiations, the most dangerous confrontation took take place on the high seas.

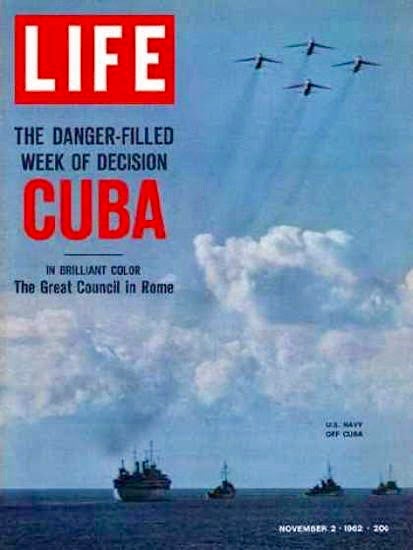

To enforce the quarantine, President Kennedy had dispatched the USS Randolph [CVS-15] and 11 U.S. Navy destroyers to Cuban waters on October 22. Their job was to enforce a blockade of Soviet ships and turn them back.

Unbeknownst to the U.S., the Soviets had sent a flotilla of four Foxtrot Class, diesel-electric submarines to Cuba on October 1st in support of the missile shipments. With the U.S. ships and Soviet submarines in such close proximity, the situation escalated dangerously.

A couple of events took place on Saturday, October 27, that together, nearly started WW III.

The first happened when Air Force Major Rudolf Anderson, piloting a U-2 over eastern Cuba, was shot down by a Soviet S-75 surface-to-air missile. The U.S. knew that the SAMs were manned by Russian crews and therefore concluded that Khrushchev must have ordered it. Years later, it was revealed that the Russian missile crew had acted on its own and that the Soviet Premier had been furious over their actions. None of this was known at the time. Kennedy’s Assistant Secretary of Defense, Paul Nitze told the President, “They’ve fired the first shot.” to which the President replied, “We are now in an entirely new ball game.”

That same day, an even deadlier situation developed between a U.S. Navy destroyer and a Soviet submarine. The USS Randolph had detected the Soviet submarine B-59 near Cuba. The destroyer, USS Cony [DD-508] was sent to investigate. Following standard procedure for the Navy during those cold war encounters, the destroyer dropped small, practice depth charges such as those used in training. Those held small amounts of explosives and were not designed to cause damage. The purpose of the small depth charges was to force the diesel submarine to the surface for positive identification. However, B-59 had been submerged for some time with its air conditioning system out and with no source of fresh air. The captain and the crew were exhausted and suffering from oxygen deprivation. There had been no radio contact with Moscow since they submerged and they did not know if war had started. With the submarine’s condition bad and deteriorating, the commander, Captain Valentin Savitsky, ordered his crew to arm its nuclear torpedo and get ready to launch it at the Cony. If that had happened, the 15 kiloton nuclear warhead, about the size of the Hiroshima bomb, would have obliterated the Cony , causing a retaliation by the U.S. that would have probably started a nuclear war.

History can never truly explain the irony of what happened next aboard B-59. Each of the four Soviet submarines carried nuclear torpedoes. A nuclear torpedo could only be launched by the submarine commander with the approval of the next senior officer, who was usually the Political Officer. The B-59 carried the Flotilla Commander, Vasily Arkhipov onboard, and because of that, all three senior officers had to approve the launching of “the special weapon.” After the political officer concurred with Savitsky’s order to launch, Arkhpov refused. He knew that the captain was stressed and exhausted. He was finally able to convince Captain Savitsky to bring the submarine to the surface.

Once they were on the surface, B-59 realized that, with Cony cruising peacefully, just 200 yards away, there was no “war”. At nine o’clock at night, with all their hatches open to bring in fresh air and with their diesel engines recharging the depleted batteries, Captain Savitsky glared at the Cony. The destroyer had put its spotlight on the submarine further aggravating its skipper. Before the Cony could establish communications with the sub, a Navy P2V patrol plane dropped explosive flares to activate its onboard cameras. At that moment, Savitsky, fearing he was under attack, turned and pointed his torpedo tubes at Cony. An officer aboard the destroyer was quickly able to get the sub’s attention, assuring them that they were not under attack. At that point, the submarine closed its torpedo doors and resumed course. In an effort to make amends, the destroyer asked if they could assist the submarine in any way. Captain Savitsky asked for some fresh bread and cigarettes which were quickly sent over to the sub. After the incident, all the Cony’s crew was sworn to secrecy. Not until 40 years later, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, was the crew able to learn just how dangerous their encounter had been.

Meanwhile, on that same Saturday night, President Kennedy was finally able to reach a tentative agreement with Khrushchev. The U.S. would remove its Jupiter missiles from Turkey and all of the Soviet missiles would be dismantled and removed from Cuba. The U.S. would not make a public statement about the missiles in Turkey, but privately agreed to do that. The White House portrayed the withdrawal of missiles from Cuba as a victory for the President’s tough stance in the face of Soviet aggression.

Sometime after the crisis was over, Theodore Sorenson, Special Counsel to the President, referred to that October 27th as “Black Saturday. President Kennedy gained international acclaim for his patient, steadfast, handling of the crisis.

If there was any hero to come out of The Cuban Missile Crisis , it was Soviet Naval Commander Vasili Arkhipov. His refusal to approve the launch of a nuclear torpedo probably prevented a nuclear war. That brave, heroic act was remembered 55 years later on October 27, 2017, in London, UK. The inaugural Future of Life Award was presented to Arkhipov’s family by the Institute of Engineering and Technology.

President Kennedy was tested by the events of October 1962. Credit for the peaceful resolution of the crisis goes to both the President and Premier Khrushchev. They both learned from the crisis and several far-reaching events occurred as a result. The first Nuclear Test Ban Treaty was signed in 1963 and the first “hotline” between Washington and Moscow was installed that year. In a different tone from some of his other cold war speeches, President Kennedy said the following to the country in May 1963: “For in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal.” Sadly, that last point would be driven home just six short months later.

John Vick

[Sources: The John F. Kennedy Library; Task and Purpose magazine article dated Sep. 4, 2016 by Gary Slaughter; Wikipedia; The Wilson Center digital archives; The National Security Archives, The George Washington University article, “Anatomy of a Controversy” by Jim Hershberg , Spring 1995; “The Week the World Stood Still” by Sheldon M. Stern; “One Minute to Midnight” by Michael Dobbs]