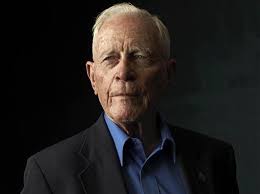

The story of Dr. Sidney C Phillips, Jr. PFC USMC WW II Veteran Part 1

Published 5:21 pm Friday, July 10, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: John Vick

The HBO miniseries, The Pacific premiered in 2010. Produced by Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg, the 10-part miniseries followed several Marines as they fought in the Pacific War. From Guadalcanal, all the way through Okinawa, the series followed three US Marines

as they fought their way across the Pacific. Although not one of the three primary Marines whose stories were followed, PFC Sidney Phillips, had a big part in the series. Actor Ashton Holmes played Phillips.

Sidney Clarke Phillips, Jr. was born in Mobile, Al. on Sep 2, 1924. His parents were Sidney Clarke Phillips, Sr. and Katharine Tucker Phillips. He had an older sister, Katharine and would have a younger brother, John. Sid went to Mobile schools and graduated from Murphy High School in 1941. Sid’s father, a WW I veteran, became principal of Murphy HS in 1942.

Growing up, Sid was best friends with Eugene Sledge, another Marine and author of “With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa”. On the day after the Pearl Harbor attack, Eugene and Sid were incensed and vowed to enlist and get revenge. They both were 17 and both needed their parent’s signature before they were allowed to enlist. Sledge’s parents refused to sign so he had to wait another year or two. Sid’s parents agreed to sign so he went downtown to join the Navy. As Sid tells it, “I wanted to join the Navy but the line was too long. That’s a hell of a way to decide, but I wasn’t very smart.” Sid enlisted in the Marine Corps later that day on Dec 8, 1941. The Marine recruiter pledged to put Phillips “eyeball to eyeball with the Japs”. Looking back, years later, Phillips said “That’s the only thing that recruiter didn’t lie about”. He was inducted later that month and shipped out to Parris Island, SC for basic training. That was where young men were made into Marines. When the new recruits arrived, they were put into formations for marching to their quarters. Other Marines, upon seeing the new recruits, would shout “You’ll be Sor-ree”. That taunt became the title of Sid Phillip’s book about his wartime experiences. After having their heads shaved, they were issued a steel bucket with toiletry articles and told they would be charged $25. for it. Realizing that their pay was only $21. per month, that phrase “You’ll be Sor-ree” started to make sense. Thinking back on Parris Island in his later years, Sid Phillips recalled a feeling that first appeared there but would stay with him throughout the war: “A strange feeling frequently came over me that was to return repeatedly during the war. It is very difficult to express in words. It was a feeling of safety in the power of armed might.

…..I would feel secure because of the trained warriors surrounding me….There was danger all around, but also a sensation of safety in what you were part of….It definitely all began at Parris Island where natural selfish concern for oneself was blunted…You knew your companions were well trained, physically strong, and could, and did get mean as hell.”

Phillips and his group of newly minted Marines were moved to New River, NC [later named Camp Lejeune] for weapons training. They finished after a few months, and were sent by train to the west coast. There they boarded a Navy transport ship, the USS Elliott [AP-13], that took them to Wellington, New Zealand arriving in July. For an Alabama boy, July in New Zealand was nothing like July in Mobile. It was winter there and Phillips said, “In my memory, those ten days in New Zealand stand out as some of the roughest duty I ever endured in the service”. Some big operation was afoot. Ships were being loaded and unloaded. All of the Marine’s weapons, ammunition and other essential gear had to be split among the different ships in the convoy. Combat loading, as it was called, insured that no one ship that was sunk would take all the trucks, tanks etc. to the bottom. It fell to the Privates [Pvts] and Privates First Class [PFCs] to do all the loading and unloading. Amid the freezing cold and sleet, the work went on for 10 days. During this time, Phillips became close friends with another Alabama boy,

Deacon Tatum. The influence of the 23 year old Tatum upon the 17 year old Phillips, was keenly felt. “The Lord had been looking out for me when He placed me in the company of Deacon Tatum”. The older Tatum was a positive influence on Phillips. Tatum had been studying for the ministry before the war. Phillips recalled, “He constantly lectured me on my sinful nature and tried to direct me to the straight and narrow…..I can remember the many times I looked deep into his eyes during naval bombardment and air raids and saw the strong faith evident there that helped me so very much.”

After 10 days, the Elliott weighed anchor and joined a large convoy headed for the island of Guadalcanal. The troops were told very little about Guadalcanal, just that the Japanese had almost finished constructing a large airfield there which could bomb the sea lanes between the US and Australia. Phillips relates, “We had always been told we would land on beaches and be almost immediately relieved by the Army….We had no idea we were the only US troops anywhere near the area….and in the opinion of the high command, the only US troops that were combat ready – which we certainly were not. No amount of mock training could ever really make men combat ready. There is just no substitute for the real thing., when you know somebody is trying his very best to kill you”.

The Marines were told that this amphibious landing would be the first real ship-to-shore landing in history, and worse yet, they were even sure if it would be successful. The standard Marine amphibious landing worked this way: troops climbed down the sides of the troop ship by way of cargo nets, into small landing craft [LCVPs, Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel, sometimes called Higgins Boats, named for the builder in New Orleans, Andrew Higgins]. As each LCVP was loaded, it would join others, orbiting in circles until all were loaded and ready to go ashore. They would then proceed, line abreast, until they offloaded the troops at the beach. Sometimes, in large invasions, the wait-time orbiting in heavy seas was lengthy and most of the troops were seasick before even going ashore.

Phillips and the other Marines were relieved when their landings were unopposed. Still, just lugging the 81mm mortar and equipment around meant that Phillips was always carrying in excess of 100 lbs. extra weight. They headed inland, through dense jungle, until they neared the airfield. There they set up gun pits and foxholes. At night, they were treated to fireworks offshore. The large Naval battle, later called, the Battle of Savo Island, would result in one of the largest defeats for the US Navy. Throughout the Battle for Guadalcanal, the Japanese tried to bring in troops for a counter invasion. The amphibious Task Force 61, led by Vice Admiral Frank J Fletcher, was supposed to bring in supplies after landing the Marines on Aug 7, and to also provide ground cover with aircraft from the carriers. Because of the heavy bombardment of the landing forces by Japanese bombers from Rabaul, Adm. Fletcher, feared for the safety of his aircraft carriers, and ordered his remaining ships to leave on the night of Aug 8. This left Phillips and the other Marines feeling that they had been abandoned. As the battle lasted on through August, the Marines were subjected to Naval bombardment nightly by Japanese cruisers and destroyers. To make matters worse, the bombers from Rabaul made daily raids while Japanese Zero fighters strafed the Marine positions. Food was in short supply since most of the ships with supplies had left on the 8th. About all they had to eat was captured Japanese rice. Phillips recalled a sign someone [in jest] placed in the mess hall, “On it was listed the entrees like: Jap rice without corned beef, Jap rice without peaches – and you could choose whatever you wanted from the menu.” Prior to Aug 20, the Marines had virtually no US aircraft support. Phillips recalled the constant danger, “There was never a moment’s rest. Something disturbed you every 20 minutes. The Japanese loved to fight at night and they loved to irritate you. One of their planes -Washing Machine Charlie, that’s what we called him-flew over almost every night, dropping flares and an occasional bomb. You finally got to where you could sleep through it. When the airfield was finally secure, US aircraft were flown in, turning a nearly hopeless situation around. Before the aircraft arrived, Phillips recalled that one of their infantry patrols had been ambushed. He remembered the brutal ferocity of the Japanese soldiers. When a company of about 300 Marines were sent it to recover their dead comrades, they found an atrocity, so horrible, that it changed the Marines attitude about taking prisoners. When they returned, they were asked about the dead Marines. They replied that “The dead Marines had all been beheaded, with their genitals severed and stuffed into their mouths”. Pfc. Phillips recalled that “after that event, my battalion never again took a Japanese prisoner. The hatred for the Japanese was a genuine emotion by all Marines of my battalion”. When the fighting subsided later that month, the order came down to bury the Japanese bodies that had piled up around their area. The Marines forced the few Japanese prisoners and Korean laborers to gather 1,000 plus corpses and place them in a burial pit. By now the physical condition of the Marines was dire. Again, Phillips recalled their overall health “What stood out in my mind was thousands and thousands of men with dysentery and diarrhea and no toilet paper. We tore out clothes, our socks, our shoes, whatever we had to use. A lot of guys couldn’t even stand up, they were so emaciated. There was no medicine, not even paregoric. They gave us Atabrine for malaria, which turns your skin yellow”. He continued, “We were completely worn out, exhausted. Most of us were in rags. We couldn’t believe we were surviving and were gonna get off that place.” Their next stop would be Melbourne, Australia for rest and recuperation. [To be continued in Part 2].

John Vick

[Sources: Dr. Sidney Phillips’ Jr. wartime memoirs, “You’ll Be Sor-Ree”; Parade Magazine, “A Fight to the Death” by Hugh Ambrose {2010}; History.net {Steve Santoro}]