The Battle of Midway – – Turning Point in the War against Japan

Published 6:48 pm Friday, June 12, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: John Vick

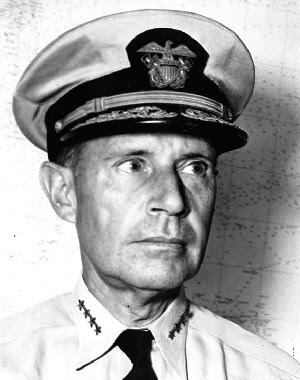

Adm. Raymond Spruance , Commander Task Force 16 at Midway

Adm. Frank “Jack” Fletcher, Overall Tactical Commander at Midway

The Battle of Midway was fought Jun 3-7, 1942, some 78 years ago. Even though it was early in the war with the Japanese, many historians point to the Battle of Midway as the turning point. After bombing Pearl Harbor, Japan had its own way, taking British Commonwealth and Dutch possessions by Mar 1942. The capture of Malaysia, Singapore and the Dutch East Indies left only the US held Philippines in the way of Japanese conquests in the South Pacific. The Philippines were officially lost with the surrender of Corregidor on May 6.

The next phase set out by Japanese Imperial Headquarters, would be to isolate and neutralize India and Australia. The planned invasion of Port Moresby in Australia was to take place May 7-8. In what came to be called the Battle of the Coral Sea , US Naval carrier forces fought the Japanese to a stalemate, postponing the invasion of Australia. This battle was remarkable because it was the first ever sea battle fought by naval ships that never came within sight of each other. It was also the first battle between aircraft carriers. The US lost the USS Lexington

[CV-3], and the Japanese lost the light aircraft carrier Shoho. The battle was also significant because of the role of US cryptanalysts, who provided vital intelligence to US commanders. The work done by those cryptanalyst would play a critical role in the next large battle, the Battle of Midway.

The Naval Intelligence station at Pearl Harbor was called Station Hypo. It was run by Navy Cdr. Joseph J Rochefort and Lcdr. Edwin T Layton, who was staff intelligence officer for the Pacific Fleet. Station Hypo had picked up Japanese communications, indicating a future invasion at a location, AF. Not sure of the location of AF, Pacific Fleet Commander, Adm. Chester Nimitz instructed the Naval base on Midway to transmit a message in the clear [not coded] back to Pearl Harbor saying that they had problems with their evaporators [which make fresh water]. Shortly after that, Hypo picked up a Japanese communication saying that AF had evaporator problems. For Adm. Nimitz, this was enough information to plan for the battle.

The Japanese planning for Midway was carried out by Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, the same Japanese commander who had planned and carried out the attack on Pearl Harbor. His plan was to entice the US Pacific Fleet into a decisive battle against his superior numbers. The hoped for defeat would cause the US to sue for peace.

Yamamoto’s plan called for a simultaneous attack on the Aleutian Islands, near Alaska. The capture of the Aleutians would prevent the US from launching long range bombers from there. The Aleutian attack was not part of Yamamoto’s original plan but he was forced to add it, in order to gain Japanese Army support for the Midway attack. The enormous Japanese naval force was divided into four battle units, none of which could support each other once the attack began. Yamamoto would command the entire operation, the Aleutians and Midway, from his flagship, the massive battleship, Yamato . This division of his forces resulted in the loss of numerical superiority for Yamamoto. His flagship would be located some 300 miles from the Japanese carrier force, commanded by Adm. Nagumo. The carriers, along with a few submarines, would be the only one of the four Japanese Naval units to take part in the Battle of Midway. The Japanese had changed their naval codes just before the battle, forcing Adm. Nimitz to plan an ambush on the Japanese fleet without knowing their exact location. Another problem for Nimitz was the unavailability of Adm. William F [Bull] Halsey, his most experienced Naval commander. Adm. Halsey was back in Honolulu suffering from severe dermatitis. In his place, Nimitz chose Radm. Raymond Spruance to command the carrier task force. Spruance was not a carrier commander, so Nimitz named Radm. Jack Fletcher, overall commander of the task force.

The overall US Commander of the Pacific Fleet was Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz. He had at his disposal three aircraft carriers at Midway ; Yorktown [CV 10], Enterprise [CV 6] and Hornet [CV 8]. The Japanese had four carriers, Kaga, Soryu, Hiryu and Akagi.

Adm. Nimitz was fortunate that all three carriers were available. Hornet had just carried out the Doolittle Raid on Japan on Apr. 18 and had returned to Pearl Harbor for replenishment of supplies and ammunition. Yorktown was damaged during the Coral Sea battle and had returned to Pearl on May 26 for extensive repairs, estimated to take two weeks. However, 48 hours later, she was able to depart from Pearl on May 28 in company with Hornet as part of Task Force 16. Their orders were to join Enterprise near an arbitrary spot designated “Point Luck”, some 325 miles NE of Midway. Point Luck was an “educated guess”, but it was hoped that the US carriers would be able to carry out an ambush from the Japanese flank.

Early on the morning of Jun 3, a US Navy scout plane [PBY-5A Catalina] located part of the Japanese transports some 700 miles west of Midway. Later that day, 6 Army B-17s were sent out to bomb the transports but were unable to achieve anything other than near misses. Another Navy PBY was sent out early in the morning of Jun 4 and reported the first contact with the Japanese carrier force, some 200 miles NW of Midway. The early warning allowed Midway to get all its aircraft in the air and to bring its defenses to battle readiness. The combined Navy, Marine and Army aircraft that had left Midway to attack the Japanese carriers met with disaster. The US planes arrived at different times rather than as a combined mass attack. Most of the Navy and Marine bombers and torpedo planes were picked off by the superior Japanese fighters. The Army B-17s were bombing from 20,000 feet and were totally ineffective.

At this point, the battle was going badly for the US. The Task Force Commander now decided to launch all available aircraft based on the approximate location of the two Japanese carriers. Planes from Enterprise and Yorktown headed for that location. Hornet sent its planes in a different direction, one that turned out to be wrong. The battle was now set – two US carriers against 4 Japanese carriers.

The first attack on the Japanese carriers was carried out by Torpedo Squadron 8 [VT-8] from the Hornet .They located the carriers and proceeded to attack. The TBD Devastors were sitting ducks with their slow, straight line approach for a torpedo run. The squadron commander was Lcdr. Jack Waldron. He bravely led his 15 planes in to the attack. Normally, a torpedo attack would be protected by fighter escorts. There were none in this case and the Japanese made mincemeat out of the US torpedo planes, shooting down all 15 planes. Lcdr. Waldron was killed along with 29 of the 30 men of VT-8. The lone survivor was Ens. George Gay, who survived and watched the battle while floating in his life vest. Despite its lack of success, VT-8 had caused the Japanese, who had been arming their planes for an attack on Midway, to bring their planes below to rearm them for carrier attack. That decision by the Japanese meant that most of their planes were on the deck or hanger bay and were sitting ducks. Because of the torpedo plane attack, the Japanese fighters flying above their ships as Combat Air Patrol [CAP], were drawn down low and were in no position to defend against the US dive bombers.

The Enterprise air group commander was Lcdr. Wade McClusky. His Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers headed toward the Japanese carriers, based on the latest intelligence. The carriers were not there and McCloskey’s planes were reaching their maximum range for a safe return to their carrier. On a hunch, McCloskey started a box search and on the second leg, spotted a Japanese destroyer, the Arashi , steaming north at flank speed. Reasoning that the destroyer must be headed to rejoin the carrier force, McCloskey ordered his planes to head in the same direction. The Japanese carriers were located and the attacks began.

With an almost open sky above the Japanese carriers, McCloskey ordered his planes to attack, and amid the confusion, all 31 planes dove on the Kaga. Lt. Dick Best, who was flying with McCloskey’s group, realized the mistake and took two of his men north to attack the Akagi .McCloskey’s group hit the Kaga with several bombs, with one bomb striking the bridge, killing the carrier’s commander and senior officers. Meanwhile, Lt. Best hit the Akagi , penetrating the deck into the main hanger below, causing a massive explosion and fires. With two Japanese carriers fatally hit, it was the turn of Yorktown’s VB-3 dive bombers led by Lcdr. Max Leslie who had left Yorktown one hour after McCloskey’s group left Enterprise . Leslie’s 17 dive bombers dropped several bombs on the third carrier, Soryu , and it sank later that evening. What Japanese aircraft that had not been shot down or destroyed while still on the carriers, were left with only carrier on which to land, the Hiryu . Late that same afternoon, Hiryu was located by a scout plane from Yorktown . Enterprise launched dive bombers who located the Hiryu and damaged it with several bombs. The Japanese abandoned ship and scuttled the Hiryu. Adm. Yamaguchi, the task force commander, chose to go down with the ship along with the ship’s Captain. This act of seppuku, by Adm. Yamaguchi, cost the Japanese their most experienced carrier commander.

While US planes attacked the Japanese carriers, Yorktown came under attack by Japanese bombers and a submarine. Yorktown was damaged and developed a 23 degree but was kept afloat by her damage control teams. On Jun 6, Yorktown was taken in tow by the fleet salvage tug, USS Vireo [AM-52]. Late that same day, the Japanese submarine I-168 found the Yorktown and fired a salvo of torpedoes, two of which struck Yorktown . A third torpedo struck the destroyer USS Hammann [DD-412] , which had been providing auxiliary power to salvage crews aboard Yorktown . The repair crews aboard Yorktown were evacuated and the carrier sank, early on the morning of Jun 7. The torpedo that struck Hammann caused her to break in half and killing 80 of her crew.

While Adm. Yamamoto still had numerous ships available, he was crippled without his carriers and their aircraft. On Jun 5 he left the battle and began a westward retreat. The US fleet attempted to follow but were forced to break off due to bad weather. On Jun 6, the weather cleared and planes from Hornet were able to sink the heavy cruiser Mikumo, while damaging a destroyer and the heavy cruiser Mogami . This last attack by Hornet ended one of the most important and decisive Naval battles in history.

The results of the US victory at Midway cannot be overstated. Midway atoll had been maintained as a base for US Naval operations in the western Pacific. The loss of four of its major aircraft carriers as well as the experienced air crews, crippled the Imperial Japanese Navy so that it never fully recovered. Their aircraft losses numbered over 290 and they lost over 2,500 personnel [including those from the heavy cruisers]. Among the air crews lost were some the most experienced pilots in the Japanese Navy.

US losses included Yorktown and Hammann, 145 aircraft and 307 personnel. As bad as those losses were, the US ability to recover was dramatically demonstrated during the Battle for Saipan , some two years later. During this battle the US Navy was able to attack with 24 aircraft carriers.

John Vick

[Sources: Encyclopedia Britannica; The History Collection; History.net; Naval History and Heritage Command; The National WW II Museum; History.com; “Joe Rochefort’s War” by Eliot Carlson; “Incredible Victory – The Battle of Midway” by Walter Lord].