Remember when: Polio epidemic of the 1950s

Published 12:00 am Saturday, March 28, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The history of polio infections extends into pre-history. The disease has been traced back to almost 6000 years. The first major outbreak of polio occurred in the U. S. in 1916. Also known as poliomyelitis, polio caused widespread panic beginning in the late 1940s.

In 1952, the polio epidemic was the worst outbreak in the nation’s history at the time. 3,145 died and 21,269 were left with disabling paralysis. Outbreaks in the United States increased in frequency crippling an average of more than 35,000 people for several years. Parents were frightened to let their children go outside especially in the summer when the virus seemed to peak. Polio was once one of the most feared diseases in the U. S. in the early 1950s. It focused on public awareness of the need for a vaccine.

Following the introduction of vaccines, the Salk vaccine, Inactivated Polio Virus (IPV) intramuscular injections, was made available in 1957 and a few years later, the Sabin Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV) was developed resulting in a decline of the number of cases.

The number of polio cases fell rapidly to less than 100 in the 1960s and fewer than 10 in the 1970s. Although polio has been eliminated from most of the world, the disease still exists in a few countries in Asia and Africa. Even if you were previously vaccinated, physicians warn that a one-time booster may be needed before you travel anywhere that could put you at risk.

Polio is an infectious disease caused by viruses that attack the nervous system. The viruses are only spread human to human by direct and indirect contact. Symptoms and signs of

polio vary from no symptoms to limb deformities, paralysis, difficulty breathing, inability to swallow foods, and death.

According to the CDC (Center of Disease Control), it is possible to prevent polio by vaccinations, and it may be possible to eradicate polio since great strides have been made.

According to the WHO (World Health Organization), 1 in 200 polio infections will result in permanent paralysis.

Cases of polio peeked in the U. S. in 1952 with 57,623 reported cases. Since the Polio Vaccination Assistance Act, the U. S. has been “polio free” since 1979.

In 1921 Franklin Delano Roosevelt became permanently paralyzed from the waist down (whether from polio or Guillain-Barre’ syndrome). Roosevelt who had planned a life in politics refused to accept the limitations of his disease, and he became the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 to 1945. In 1938, FDR founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis now known as the March of Dimes who sought small donations from millions of individuals.

Growing up in the 1950s, here is what I remember about that polio scare when I was a child. In the summertime, the children in my family and my friends in the neighborhood had to take about an hour nap. Because there was no air conditioning in the early 1950s, windows were open, and we could only hope for a breeze! Later on when we went swimming or got soaking wet under the water sprinkler, it was necessary and important that we dry off quickly because of the polio epidemic and the danger especially to children.

My mother and many of her friends with children joined the March of Dimes as volunteers and would go around the neighborhoods and businesses asking for small donations. There would usually be a chairman. Those “dimes” were attached to a cardboard type card that I can visualize today exactly what it looked like. When a number of cards were filled, they were forwarded to the March of Dimes headquarters. There was even a drive at school for each child to bring a dime. Civic clubs would participate. The effort was widespread across America.

The next thing I vividly remember about polio was that polio shots were administered at school. I must have been a difficult student since my mother was called to come to school to hold me down! I ended up pulling her maternity top off. That must have been about 1955 since my sister Julie was born that year.

Those shots were big, and the liquid in the injection looked like thick non-dairy whipped topping! There was not just one injection. There were two that were given to school children a few months apart. Lordy!

Then into the 1970s, the local Coterie Club of young ladies used to send club members to the Scherf Memorial Building to volunteer at the Crippled Childrens’ Clinic in the downstairs area. I recall that a doctor would travel from Pensacola to work at the clinic several times a month. There must have been enough children affected in the surrounding counties to hold a regular clinic in Andalusia.

My good friend Dan Shehan, former English teacher for many years at the Andalusia High School, suffered from an attack of polio as a child. I asked him this week to send me his story. I will share a portion with you readers.

“I had just finished the 5th grade at Parker Elementary School in Panama City, Florida. I was 10 years old and had been spending the summer with my maternal grandmother, Lilly D. Everage, on East Watson Street in Andalusia, the town of my birth. Several of her grown children lived nearby. One owned a grocery store on Stanley Avenue a block away. I would walk to the store in the mornings and get the food she planned to cook that day. If it were peas and butterbeans, I would help shell them. In the afternoons, I would walk to one of the theaters, pay 25 cents, and sit through the showing several times.”

“One morning in August 1953, I awoke with a stiff neck and terrific headache. As the day progressed, I began to feel very weak. The next day, I could hardly get out of bed or stand up without help and was admitted to Covington Memorial Hospital. My parents, Comer and Helon Everage Shehan, were called, and they drove up from Panama City. Dr. Parker didn’t know what I had at the time. By that evening, I could not even move, and my breathing had become very shallow. My parents decided to place me in the back seat of the car and drive me to a Pensacola hospital where a relative had arranged for a doctor to meet us at the emergency room.”

“I was placed on an examining table and told to be very still for a spinal tap. After the procedure, the doctor and the nurse left the room and I was alone since my parents weren’t even allowed in the room. While lying there wondering what was the matter, I heard a scream from another room. I was put on a stretcher a little later, placed in an ambulance, and driven to another building in the dark of night. I was very thirsty and semi-conscious, but the nurse would only put a drop of water on my tongue all along. I had not seen my parents since arriving at the emergency room. I thought whatever was wrong with me must be so bad that I was being put to death!”

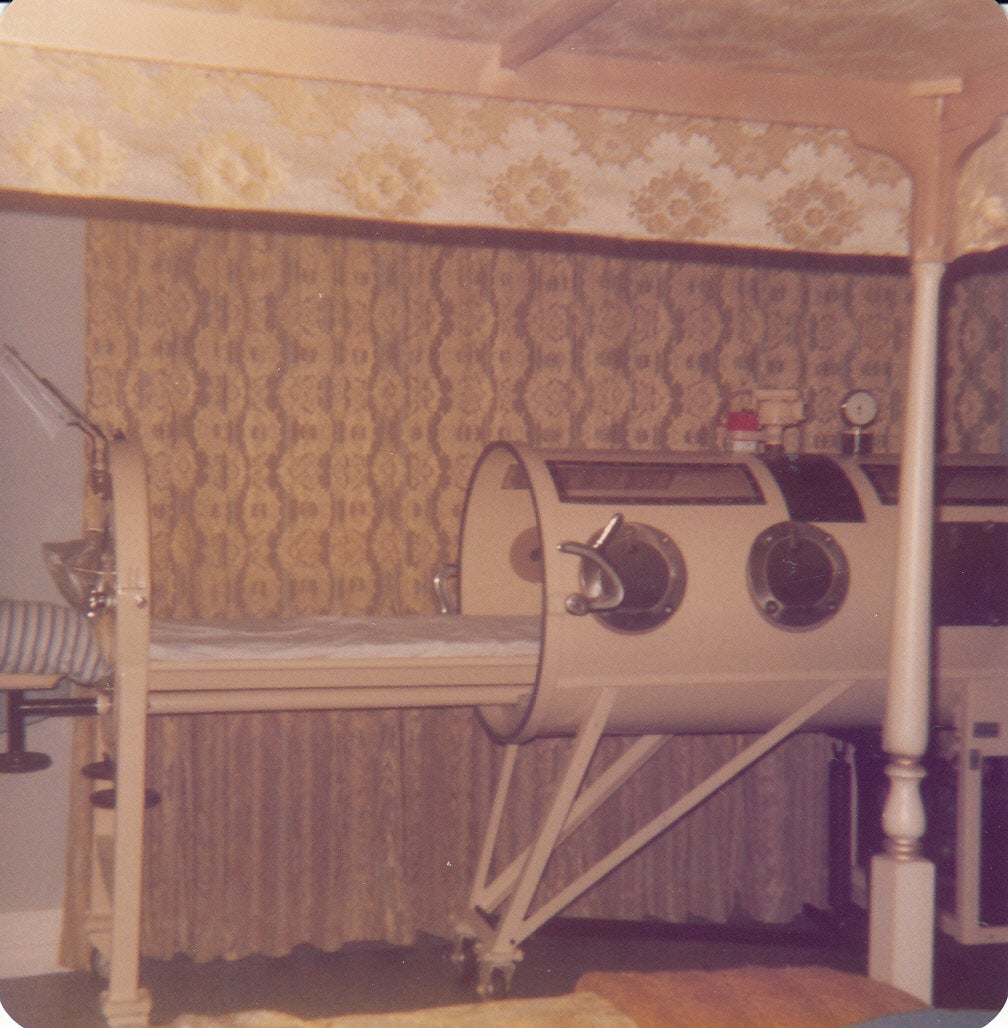

“When I finally awoke the next morning, I found myself enclosed in a tank-like contraption with my head sticking out one end. I soon learned that is was called an iron lung. I was feeling much better and had no trouble breathing although I was unable to move my arms and legs. As I shifted my eyes to the left, I saw rain through one of the high windows. To the right, I saw my parents looking through a window at me. I wondered what was going on.”

“Unknown to me at the time is what had transpired during the night. After the spinal tap, the doctor met with my parents and relatives and gave them the news that I had Bulbar polio and would be dead within 24 hours. Mother is the one that had screamed. She would not accept the prognosis. She phoned her brother-in-law, Dr. Robert Earl Vickery, who was a student at the University of Alabama Medical School in Birmingham. He and one of his professors flew down to Pensacola to the Escambia County Hospital during the night. They asked if there was an iron lung in the hospital. The reply was yes, but no one knew how to use it! My uncle and his teacher had put me in the iron lung thus saving my life!”

This story gets more intriguing and will be continued in next week’s Remember When column. Thank you Dan Shehan, native Andalusian now residing in Savannah, Georgia.

Sue Bass Wilson, AHS Class of 1965, is a local real estate broker and long-time member of the Covington Historical Society. She can be reached at suebwilson47@gmail.com.