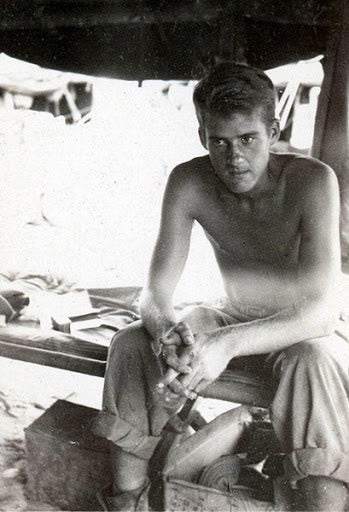

Part 2: Eugene B Sledge, Marine, WW II Veteran, Author and College Professor

Published 10:44 am Wednesday, March 25, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

BY JOHN VICK

In Part 1 of this tribute to the late, Eugene B Sledge, native of Mobile, AL, and legendary Marine, the narrative stopped as Sledge and his K Company, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines were returning to Pavuvu. In Nov 1944, that weary group of Marines were given a short break from the blood bath of Peleliu. There was no time for rest, as the new replacements for those men lost on Peleliu, had to be trained and absorbed into the ranks. The Battle for Peleliu held special significance for the Marines of K/3/5 – and it has been so through the many intervening years. Okinawa, which they would invade in a few short months, held a new challenge, without the same rules as they had become accustomed in their previous island-hopping campaigns.

Sledge and the rest of the survivors from Peleliu reached Pavuvu on Nov 7, 1944, three days after his 21st birthday. Besides the many friends that had been lost, one loss grieved Eugene Sledge the most – that of his beloved Company Commander, Capt. Andrew A Haldane. Said Sledge, “Never in my wildest imagination had I contemplated Capt. Haldane’s death. We had a steady stream of killed and wounded leaving us, but somehow I assumed Ack Ack was immortal. Our company commander represented stability and direction in a world of violence, death, and destruction……We felt forlorn and lost. It was the worst grief I endured during the entire war. The intervening years have not lessened it any…..the loss of our company commander at Peleliu was like losing a parent we depended upon for security – not our physical security, because we knew that was a commodity beyond reach in combat, but our mental security. …We had lost our leader and our friend. Our lives would never be the same. But we turned back to the ugly business at hand”.

Much of the training before Okinawa took place on the island of Guadalcanal. The name of that island was embroidered in white letters down the red number One of the 1st Marine Division’s patch. Guadalcanal was the first major land offensive against Japan, having begun in Aug 1942. Somehow, there was great symbolic significance for the 1st Marines, as they prepared for what would be the largest and deadliest of all WW II battles in the Pacific

A large convoy, making up part of the Okinawa invasion force, sailed with Sledge and the Marines from the Russell Islands on Mar 15, 1945. They were bound for the Ulithi Atoll where they would join up with many more ships that would make up the largest invasion force in the history of the war. Okinawa stood alone, as the last defensive piece on Japan’s chessboard. The battle there, would be unlike anything the Navy and Marines had experienced thus far.

Sledge and K Company joined many thousands of soldiers and sailors, on the morning of Apr 1, 1945, for Operation Iceberg, the invasion of Okinawa. The significance of Apr 1st being D Day Okinawa, far outweighed the fact that it was Easter Sunday as well as April Fool’s Day. The battle plan briefings had warned the men hitting the beach, that they would probably “get the hell kicked out of them”.

Instead, the landings were largely unopposed. As the men advanced inland from the beach, Sledge was wary, knowing the past treachery of the enemy. “It suddenly dawned on me though, that it wasn’t at all like the Japanese to let us walk ashore unopposed on an island 350 miles from their homeland. They were obviously pulling some trick, and I began to wonder what they were up to”.

Of the 50,000 troops that went ashore on D Day, only 28 were killed, 104 wounded and 27 missing. The original plan called for the 4 Divisions to cross the island, cutting it into. The Marines were to move north, securing the upper two-thirds of the island, while the Army troops were to proceed south.

Needless to say, the battle plans for Okinawa were soon scrapped. Japan had a different plan for the defense of that island. The island itself, was some 60 miles long and from 2 to 18 miles wide. It was surrounded by a coral reef. The western beaches were chosen for the invasion because the coral lay close to the shore. A ridge runs through the center of the island, reaching some 1,500 feet in the mountainous areas of the north. There were three east to west ridge systems that crossed the southern part of the island. These ridge systems were natural defensive barriers for the Japanese.

Lt.Gen. Mitsuru Ushijima, the Japanese commander charged with defending Okinawa, had some 110,000 men that he placed in the most strategic parts of the ridge system. Along with the natural barriers, the Japanese placed mutually supporting defensive barriers and pillboxes in between. They were interlocked with a connecting system of tunnels. As the invasion forces encountered each defensive line, there would be a bloody, gut-wrenching fight until the defender’s positions became untenable. At that point, the Japanese would withdraw to the next defensive line. The previous battles at places like Saipan, Peleliu and Iwo Jima, had given the defenders a sophisticated defense, born of those experiences. Their goal would be to wait, fight, inflict maximum casualties, withdraw to another defensive position – all in the hope of exhausting the resources and the will of the American forces. To make matters incredibly worse, right in the middle of the battle for Okinawa, torrential rains fell, almost bringing to a halt, the progress being made.

When the bloodiest battle of the Pacific war was officially over – it had lasted from Apr 1 to June 22. The most complete list of casualties was never officially recorded until the dedication of The Cornerstone of Peace monument at the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum. As of 2010, there are 240,931 individual names listed. Those listed as “killed”, include 14,009 Americans, 77,166 Japanese troops, 149,193 Okinawan civilians and a smaller number [S. Korea, 365 – the United Kingdom, 82 – N. Korea, 82 – and Taiwan, 34] of other nationalities.

American total casualties were over 82,000, including non-battle. Okinawa is known for the large number of casualties labeled “combat fatigue” [shell shock in layman’s terms]. Quoting from the Marine Corps Gazette: “More mental health issues arose from the Battle of Okinawa than any other battle in the Pacific during WW II. Constant bombardment from artillery and mortars coupled with high casualty rates led to a great deal of personnel coming down with Combat Fatigue. …rains and mud prevented tanks from moving and tracks from pulling out the dead, forcing Marines [who pride themselves on burying their dead in a proper and honorable manner] to leave their comrades where they lay. That coupled with thousands of bodies both friend and foe littering the island, created a scent you could nearly taste. Morale was dangerously low by the month of May and the state of discipline on a moral basis had a new barometer for acceptable behavior. The ruthless atrocities by the Japanese throughout the war had already brought on an altered behavior [by traditional standards] by many Americans….however the Japanese tactic of using the Okinawan people as human shields brought a new aspect of terror and torment to the psychological capacity of the Americans”.

Eugene Sledge was able to reminisce on Jun 21.

“We learned the high command had declared the island secured. We each received two fresh oranges with the compliments of Admiral Nimitz…..after 82 days and nights, I couldn’t believe Okinawa had finally ended.”

Sledge and the Marines were given one final task – that of cleaning out the few remaining Japanese hiding in caves – and at the same time, cleaning up the brass above .50 caliber in size and burying the Japanese dead. Cleaning out the Japanese was as dangerous as the battles had been. Quoting Sledge, “The enemy we encountered were the toughest of the diehards, selling their lives as expensively as possible. We were nervous and jittery. We were fugitives from the law of averages. A man could survive Gloucester, Peleliu and Okinawa, only to be shot by some fanatical, bypassed Japanese, holed up in a cave…..the fighting was our duty, but burying enemy dead and cleaning up the battlefield wasn’t for infantry troops as we saw it….It was the ultimate indignity to men who had fought so hard and so long and had won…..we dragged ourselves back north in a skirmish line. We cursed every dead enemy we had to bury. We cursed every cartridge case [above .50 caliber in size] we collected and put into piles.”

In cleaning out the diehard Japanese, the Marines were fortunate to have had the support of the tanks with flamethrowers. The lives of many Marines were saved. During the mop up operation, over 8,975 Japanese were killed. Arguably, the dirty job of mopping up was necessary, because that many Japanese would have been able to wage quite a guerrilla war.

In the end, Sledge [or Sledgehammer as he was called by his friends], thought about his friends of K Company who had invaded Okinawa, “Very few familiar faces were left. Only 26 Peleliu veterans who had landed with the Company on Apr 1st remained. And I doubt there were even 10 of the old hands who had escaped being wounded at one time or another on Peleliu or Okinawa…Statistically, the infantry units had suffered over 150 % losses through he last two campaigns. The few men like me who never got hit can claim with justification that we survived the abyss of war as fugitives from the law of averages”

After Okinawa, there were rumors that the Marines would hit Japan next. The War Department had estimated that an invasion of the home islands of Japan would result in over one million US casualties and a further, almost incalculable, number of dead Japanese troops and civilians.

One can only imagine the intense relief felt by the American troops when they learned that Japan had surrendered on Aug 15, 1945. Many “arm chair historians” have argued over the morality of using the atomic bomb to force the Japanese surrender. There are many Americans, and many Japanese, alive today, who owe their existence to President Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bomb.

The words of Eugene B Sledge, a survivor of this horrific war, are a timeless reminder of the lives at stake, when the US dropped the atomic bomb:

“We thought the Japanese would never surrender….sitting in stunned silence, we remembered our dead. So many dead. So many maimed. So many bright futures consigned to the ashes of the past. So many dreams lost in the madness that had engulfed us.

And finally, Sledge’s own take on the war, “War is brutish, inglorious, and a terrible waste. Combat leaves an indelible mark on those who are forced to endure it. The only redeeming factors were my comrades’ incredible bravery and their devotion to each other. Marine Corps training taught us to kill efficiently and to try to survive. But it also taught us loyalty to each other – and love. That esprit de corps sustained us.”

John Vick

Next week: China Marine – Eugene Sledge and the Marines in China.

[Author’s sources: “With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa” by Eugene B Sledge; Museum of The United States Marine Corps; Wikipedia; History.net; US Naval History and Heritage Command]