Son: Wallace’s journey was ours

Published 12:02 am Tuesday, October 23, 2012

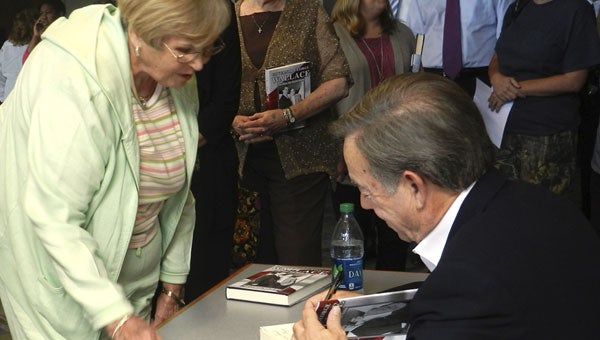

Speaking at the community college named for his mother, George C. Wallace Jr. Monday said he wrote a book about his father in hopes of correcting factual errors in the Wallace legacy.

The book, Governor George Wallace, The Man You Never Knew, tells the Wallace story from his family’s perspective. Wallace spoke as part of LBW’s free lecture series.

There is historical misconception about Gov. Wallace, his son said, especially about Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965, when 600 civil rights marchers were attacked by state and local police with billy clubs and tear gas as they crossed Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge on a planned voting rights march to Montgomery.

“My father’s orders were disobeyed,” Wallace said.

The elder Wallace was defiant, his son said. But he never advocated violence. And he was livid when it happened.

“Bob Ingram was in my father’s office when the news about the Edmund Pettus Bridge came,” Wallace said of the former Montgomery reporter and longtime political commentator. “(Ingram) wrote that he has never seen a more enraged man in his life.”

Wallace said that his father had ordered protection for the marchers as they traveled Hwy. 80 toward Montgomery, as rumors had swirled that snipers planned to hide in the woods and attack the marchers.

Similarly, Wallace said, his father’s stand in the schoolhouse door in an attempt to prevent racial integration of the University of Alabama, prevented violence.

At Ole Miss, and at the University of Arkansas, integration brought riots and deaths.

“There was not even a sprained ankle here,” he said. “My father was on TV, night after night, saying to Alabamians, ‘Stay away. I’ll raise the questions for us.’ ”

The elder Wallace was young and brash, his son said. “He was defiant, but he never advocated violence.”

When the governor stood in the schoolhouse door in defiance of federal troops, he raised Constitutional questions about the 10th Amendment and the rights of states, Wallace said Monday.

Gov. Wallace was wrong about segregation, his son said. But he was right about the federal government. Nonetheless, the issue branded him forever, his son said.

Wallace said his father was reared in a rural South that taught him that the separation of the races was best for all concerned. As an attorney and judge, the man who would rise to prominence on the national stage tried to be fair with everyone, Wallace said Monday.

When his father first ran for governor in 1958, he was considered the moderate candidate on the segregation issue. His opponent, John Patterson Jr., was a hard-liner.

“I’ve talked with Gov. Patterson about that race,” Wallace the son said. “He said that when he campaigned, he talked about economic development and roads and got little reaction.

“When he talked about segregation, they stomped the floor,” he said.

In 1958, George Wallace Sr. said, “If I can’t treat a black man fairly, I don’t deserve to be governor.”

After he lost that first gubernatorial race, he embraced segregation as his issue.

“In many ways, he turned his back on those he wanted to help most,” his son said. “But he also had so many populist initiatives that helped all people.”

Free textbooks in public schools, and a sprawling two-year college system that gave almost any citizen of the state access to higher education are among those.

While he doesn’t believe his father would have been elected president in his 1968 campaign, it appeared he had enough support to throw the election into a decision by the U.S. House of Representatives.

Campaigning as a member of the American Independent Party, Wallace at one time polled 24 percent support in a race against Humphrey as the Democratic nominee and Nixon as the Republican. Comments by Wallace’s vice presidential running mate, Gen. Curtis LeMay, who’d been his commander in World War II, sunk those ratings.

In the 1972 presidential race, Wallace, running as a conservative Democrat, won every county in Florida and ever county in Michigan. He was ahead by a million popular votes and several hundred delegates, when Arthur Bremer tried to assassinate him.

“That was his first step in his Road to Damascus,” Wallace said.

The five bullet wounds left the governor paralyzed and in terrible pain. The pain, his son believes, helped him to bond further with those he had been accused of hating.

“After that, he felt a common sacrifice with civil rights leaders of his one life’s blood,” Wallace said.

He forgave the would-be assassin, and told him so in a letter.

“I had thought about spending some Old Testament time with (Bremer), but not to pray with him,” Wallace said. “I asked my father, ‘How can you do that?’ ”

“He said, “Son if I can’t forgive him, the Lord can’t forgive me.’ ”

Wallace made efforts for the rest of his life to reconcile the hurts of his segregationist stance, his son said, recounting the time in 1979 when Wallace went to what had been Martin Luther King’s Church, as well as the personal meetings he had with leaders of the African American community.

“His journey is one we all took,” the son said. “He changed, we all changed.