Very thankful

Published 12:02 am Thursday, November 24, 2011

Angelo Agro is planning a quiet, reflective day today. For on this Thanksgiving, the list of things for which he is thankful is different than in previous years.

“I’m specifically thankful for the donor who gave me his or her lung,” he said. “It’s a remarkable thing to have someone else’s living tissue functioning inside of you. I’m thankful for the organ donation system, and that this sort of surgery can be done.”

The Andalusia ear, nose and throat specialist had rapidly progressing idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Idiopathic, he explained, means that the cause is unknown.

“It’s not genetic, but it tends to sort of run in families,” he said. “It’s not related to smoking or other things lung disease is generally related to.”

People with IPF just have bad luck, he explained.

Agro was being treated at UAB in Birmingham, but his condition was advancing so rapidly, he was referred to Duke University’s program. At UAB, the average wait for a lung is 18 months. At Duke, it’s 18 days. The program started about five years ago, and completed its thousandth transplant last year. Without it, Agro said, he’d be dead.

The program is rated the best in the country, and Agro believes that makes it the best in the world.

“They get organs from all over the country,” he said. “They are situated in just the right place, and get the best results. They are significantly ahead of the second place, which I believe is the University of Pittsburg.”

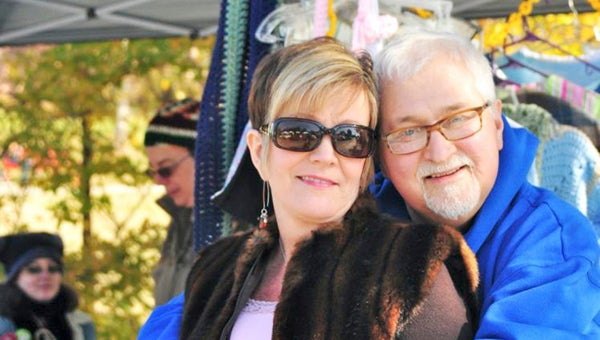

First, Duke has a high standard for acceptance into its lung transplant program. Dr. Agro and his wife, CJ, first went to Duke last summer. There, he underwent two weeks of tests.

“When they eventually make you a candidate, tell you to move up here, start at rehab in their Center for Living. It’s a huge facility dedicated to physical therapy and rehab.”

Transplant candidates must complete a minimum of 23 daily sessions.

“They have you meet some minimum performance criteria to be sure you’re in good enough shape to withstand surgery,” he said. “The surgery just about kills you.”

Agro completed his “prehab,” and was added to the transplant list on Fri., Sept. 9. The next night, at 10, he got a phone call saying “get over to the hospital.”

“When we got there, they said, ‘This one’s not for you, but don’t leave the hospital. We have another potential lung coming it.’ ”

At 9:30 p.m. on Sun., Sept. 11, he was told he’d be in the operating room in half an hour. He describes it as a mind-boggling experience.

“While you’re waiting for an organ donation, you realize a drama is being played out between surgeon, recipient and the donor,” he said. “And only two of those people know a drama is being planned.”

Agro received a lung, a heart valve and an artery from the donor. A good friend he’d met in the program got the donor’s other lung. They refer to each other as “lung brothers.”

“Here’s a person who saved two lives, at least,” he said. “It’s a moving thing to be a recipient. I am grateful.”

The experience of having one’s chest opened, a lung pulled out, and passing a second or two without a vital organ?

“It’s a mind boggling experience,” he said. “I feel I have a second chance at life. It’s like I’m starting over, reassessing my priorities, thinking about smelling the flowers and how I want to do things. It’s like going back to square one.”

Even with the prehab work, getting a lung transplant doesn’t make living a “slam dunk,” he said.

Still at Duke, every day he does one of two things.

“I either have some sort of test or doctor’s appointment, or I go to PT and rehab until they release me.”

Physical therapy is four hours, including an hour-long floor exercise class, riding an exercise bike as hard as he can go for 20 minutes, walking a track for 30 minutes, then a session with weights.

Organ recipients have a number of predictable complications.

“Everybody gets to be diabetic,” he said “You are immune-suppressed, so you are just sitting ducks for infection. The legs are weak and tired.”

But more than two months after his transplant, he’s starting to feel normal, and he’s thinking about coming home. His regimen includes 43 pills, three shots of insulin, blood thinner and antibiotics. When the side effects can be managed with pills only, and there are no signs of rejection or infection, his doctors will talk to him about coming home. Three months is the average, so he’s looking at the first of the year. Data collection and recording are an important part of recovery.

“They expect you to monitor a pulmonary function test every day for the rest of your life,” he said. “You have to monitor vital signs and blood sugar and keep accurate records every day.”

He is quick to say that his wife has been a key to his recovery.

“In the hospital, it takes about 20 people to take care of you,” he said. “When you go home, there’s one person to take care of you. CJ has been key to this system.”

There are many ways that being an organ recipient has changed his life, he said being with the person taking care of your 24-7 is eye-opening.

“CJ has been wonderful,” he said.

Today, he said, his wife is preparing leg of lamb.

“We’ll settle back and just thank God,” he said. “We are especially thankful for all of our friends, the support, fundraisers, things like that. This has been life-changing in every way, even financially.”

For every lung transplant, somebody – an individual, an insurance company, or a government insurance program – pays Duke $1.9 million.

“And there is not an insignificant co-pay,” he said. “It requires a lot of realigning.”

Right now, he’s eager to get back to work. During his recovery, he passed his sleep medicine boards, adding another specialty to the work he can do in private practice.

“My mind is ready, my body is not,” he said.

To those who have not signed an organ donation card, he’d say this:

“It’s the simplest and most elegant way to go out a hero,” he said. “Donate life. Because when you do that, to someone that you don’t even know, you will be a hero. It costs nothing. There is no pain, nothing involved, except the effort to put your name on the card.

“It’s the soul that matters,” he said. “The temporal body and the organs don’t make you you, just as this lung doesn’t make me me.

“It’s the last altruistic gesture you can make, certainly the most significant to the recipient,” he said.

“The organ donation system is something miraculous, and I’m thankful for it,” he said.